Beata Bonna

ORCID: 0000-0002-3968-9541

Uniwersytet Kazimierza Wielkiego w Bydgoszczy beata@bonna.pl

Mothers in the process of supporting a child’s musical development in the prenatal period – today and earlier

Abstract

The study showed that mothers in both groups know about the benefits of taking up musical activity during pregnancy. However, they differ in their assessment of these advantages, such as faster development of the child’s hearing and musical abilities, or the occurrence after birth of reactions to music the child knows from the fetal period. Statistical differences were also found in the responses concerning the ways of acquiring knowledge on musical development in the prenatal period. More young women sought it out on the Internet, in scientific literature, in women’s magazines, at universities, or at gynecology clinics, and admitted that they indeed had such knowledge. The respondents, however, were consistent in their assessment of the pe-riod during which the child begins to hear, and in their responses to the most important stages of the child’s musical development.

The musical activity of women during pregnancy differed in many respects between the compared groups. It was found that more women who had recently given birth engaged in it advisedly, aware of the impact of music on the child. Moreover, the respondents differed in terms of how often they engaged in singing, listening to music, moving in time to music, and attending concerts of popular music, with the young mothers again being more active in this respect. Statistically, more younger women also sang lullabies and poetry, and listened to clas-sical, popular music, rock, hip-hop, reggae, and jazz.

Further differences were related to the findings of the respondents concerning their children’s reactions to music in the prenatal and neonatal periods. It was demonstrated that more young women observed increased fetal mobility in response to music. They also noticed in their newborn children preferences for certain songs, particularly ones they knew from the prenatal period, along with such reactions as smiling, directing attention to the source of the sound, or giving the impression of listening to music. Young mothers were also more aware of the relationship between musical activity during pregnancy and after childbirth and later musical behavior.

The results obtained in the present study should be explained by the dynamic growth of knowledge on human musical development of over the past several decades, and by its

gro-Vol. 9 pp. 217–236 2020

ISSN 2083-1226 https://doi.org/10.34858/AIC.9.2020.345 © Copyright by Institute of Music of the Pomeranian University in Słupsk Received: 21.09.2020

Accepted: 26.11.2020

wing popularization. This is related not only to the increase of young mothers’ awareness of the benefits of prenatal musical stimulation of children, but also to taking specific actions, which gives hope for better use of its developmental potential.

Keywords:

supporting the musical development of a child and the age of mothers, mothers’ knowledge of selected aspects of a child’s musical development, musical activity of women during pre-gnancy, children’s reactions to music in the prenatal and neonatal period.

Introduction

Many years ago, Zoltan Kodaly claimed that the musical education of a child should begin nine months before the birth of his mother1. This remarkable opinion seems to be

confirmed by the results of research on the musical development of humans in the fetal period, which has been arousing increasing interest among scientists2. Explora tions of

the processes of gaining experience in the prenatal development phase, the influence of music on fetal reactions, and of non-invasive technologies for monitoring it have made reliable analyses of perceptual and cognitive abilities of a child possible, even before birth. Due to their influence, people began to argue that human musical deve-lopment begins already in the fetal period3. It is believed that the sounds that reach the

ear and brain of the fetus may participate in the structural and functional de velopment of the auditory tract. This may suggest that the more musically stimulating the envi-ronment of a child is in the prenatal phase of development, the more musical the child will become after birth, as her or his nervous system will be better adapted to receive, transmit, and process such stimuli4. Sounds from the intrauterine environ ment are an important developmental element in human fetal life, as they form the basis for

sub-1 E. Klimas-Kuchtowa, Znaczenie rozwoju muzycznego dla przyszłej muzykalności, in Człowiek –

muzyka – psychologia, W. Jankowski, B. Kamińska, A. Miśkiewicz (ed.), Akademia Muzyczna im. Fryderyka Chopina, Warszawa 2000), s. 311.

2 See Ruth Fridman, „The Maternal Womb: the First Musical School for the Baby”, Journal of Pre

natal and Perinatal Psychology and Health 15, 1 (2000); Richard Parncutt, „Prenatal Develop-ment”, In The Child as Musican. A Handbook of Musical Development, ed. Gary E. McPherson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006); Heiner Gembris, „The Development of Musical Abilities”, in MENC Handbook of Musical Cognition and Development, ed. Richard Colwell (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006); Joëlle Provasi, David I. Anderson, Marianne Bar-bu-Roth, „Rhythm Perception, Production, and Synchronization During the Perinatal Period”, Fron tiers in Psychology 5 (2014).

3 Michał Kierzkowski, Rozwój muzyczny dziecka w wieku przedszkolnym. Uwarunkowania, dy

namika i rola w kształtowaniu sfery psychoruchowej (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Athenae Geda nenses, 2012), 32-33; see also: Noura H. Al‐Qahtani, „Foetal Response to Music and Voice”, ANZJOG 45, 5 (2005); J. Garcia-Gonzales, M.I Ventura-Miranda, F. Manchon-Garcia, T.I. Palla res-Ruiz, M.L. Marin-Gascon, M. Requena-Mullor, R. Alarcón-Rodriguez & T. Parron-Carreño, „Effects of Prenatal Music Stimulation on Fetal Cardiac State, Newborn and Vital Signs of Preg nant Women: a Randomized Controlled Trial”, Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 27 (2017).

4 Klimas-Kuchtowa, „Znaczenie rozwoju muzycznego dla przyszłej muzykalności”, in Człowiek

– muzyka – psychologia, 313; see also: Beata Bonna, Zdolności i kompetencje uczniów w młodszym wieku szkolnym (Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego, 2016).

sequent learning and behavior. They help to stimulate brain function at a higher level of organization5. Prenatal exposure to music affects brain plasticity and enhances the

nervous response to sounds known from the prenatal period. Research indicates that fetal exposure to structured sound environments can be beneficial for supporting audi-tory processing in infants6. It is also stressed that perceptual sensitivity to the sounds

of music, appearing weeks or even months before birth, has important implications for musical education, which perhaps needs to be started already in the prenatal period7.

To date, the interest in the musical development of a child in the prenatal period has resulted in the research carried out in this field focusing mainly on the musical reactions of the fetus, while mothers are usually involved in studies as participants in experimental projects in which they exert musical influences following a previo-usly planned experimental procedure8. For this reason, focusing on the mother and

her participation in prenatal support of the child’s musical development complements investigations of this rarely explored area and justifies the present study, whose results are discussed in this paper.

The methodological context of the study

The aim of this study was to diagnose the musical activity of women during pregnan-cy, their observations related to their children’s reactions to music in the prenatal and neonatal periods, and their knowledge about their children’s musical development.

In the course of the study, the research problems were formulated as the following questions:

1. Does the women’s age make a difference in their knowledge of selected aspects of a child’s musical development, and if so, to what extent?

2. Does the age of women (at which they become mothers) make a difference in musical activity during pregnancy, and if so, to what extent?

3. Does the age of women (at which they become mothers) make a difference in their observations concerning their children’s reactions to music in the

prena-5 Tomatis; after: Giselle E. Whitwell, „The Importance of Prenatal Sound and Music”, Journal of

Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health 13, 3–4 (1999); see also: Bonna, Zdolności i kom petencje uczniów w młodszym wieku szkolnym.

6 Eino Partanen, Teija Kujala, Mari Tervaniemi & Minna Huotilainen, „Prenatal Music Exposure

Induces Long-Term Neural Effects”, PLoS ONE 8, 10 (2013).

7 Gembris, „The Development of Musical Abilities”, in: MENC Handbook of Musical Cognition

and Development, 125.

8 Jean P. Lecanuet, Carolyn Graniere-Deferre, Anne-Yvonne Jacquet & Anthony J. DeCasper,

„Fe-tal Discrimination of Low-Pitched Musical Notes”, Developmen„Fe-tal Psychobiology 36, 1 (2000); Ravindra Arya, Maya Chansoria, Ramesh Konanki & Dileep K. Tiwari, „Maternal Music Expo-sure During Pregnancy Influences Neonatal Behaviour: an Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial”, International Journal of Pediatrics (2012); Partanen, Kujala, Tervaniemi & Huotilain-en, „Prenatal Music Exposure Induces Long-Term Neural Effects”; Garcia-Gonzales, Ventura-Mi randa, Manchon-Garcia, Pallares-Ruiz, Marin-Gascon, Requena-Mullor, Alarcón-Rodriguez & Parron-Carreño, „Effects of Prenatal Music Stimulation on Fetal Cardiac State, Newborn and Vital Signs of Pregnant Women: a Randomized Controlled Trial”.

tal and neonatal periods, and if so, to what extent?

The study was carried out in the years 2015-20169 using the method of a

diagno-stic survey and the technique of a questionnaire. The data were obtained from 200 respondents from the Voivodships of Kujawsko-Pomorskie and Wielkopolskie. The selection of the study group was both random and specific. The specific aspect related to the selection of voivodeships based on good knowledge of the institutions located within their respective territories - areas in which the tested population resides, but the institutions themselves were selected randomly. The study group consisted of women aged from 18 to 35 years (N=100) and from 51 to 70 (N=100) years. A chi-squared test was used to assess the significance of the differences in the frequency distribution of the responses between the groups. The choice of groups for the study was linked to the intention of capturing and describing the changing participation of women in the process of supporting the musical development of children in the prenatal period. One also has to be aware that variables other than the age of the studied population, such as social status, could also turn out to be factors differentiating knowledge, mu-sical activity and the observations of the diagnosed women regarding the reactions of children towards music.

Results and discussion

Women’s knowledge regarding selected aspects of children’s musical deve lopment

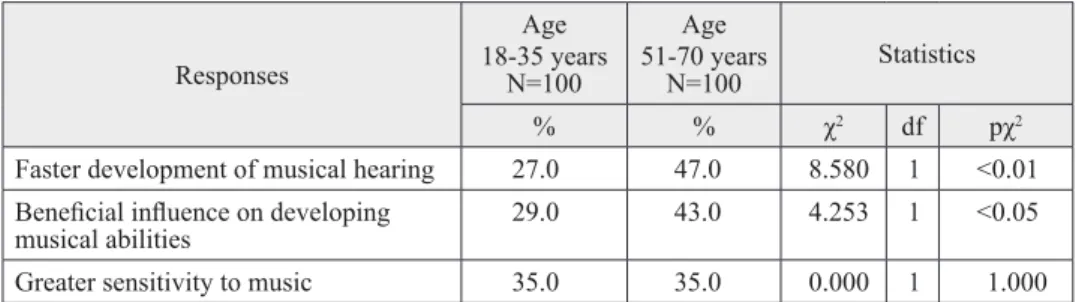

In the research perspective adopted, it seemed interesting to determine whether the women were aware of the benefits for their child’s development resulting from musi-cal activity during pregnancy.

Table 1 Benefits for the child resulting from musical activity

of mothers during pregnancy

Responses Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=100 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2

Faster development of musical hearing 27.0 47.0 8.580 1 <0.01

Beneficial influence on developing

musical abilities 29.0 43.0 4.253 1 <0.05

Greater sensitivity to music 35.0 35.0 0.000 1 1.000

9 The study was carried out by P. Pożarowska and D. Siarkowska in the diploma seminar under the

guidance of the author, who provided the original idea and participated in the implementation of this study project.

Occurrence of post-natal reactions to

music known from fetal life 57.0 33.0 11.639 1 <0.001

Positive influence on overall

development 65.0 65.0 0.000 1 1.000

Source: the author’s own elaboration. χ2 – chi-squared

df – number of degrees of freedom

pχ2 – probability based on the chi-squared test conducted p≤0,05 – significant difference

p≤0,01 – highly significant difference

In both groups, most mothers found that musical activity during pregnancy had a positive effect on the overall development of the child. It is worth noting that this

phenomenon is confirmed by a growing body of research in this area10. In addition,

women consistently claimed that prenatal experiences can make children more sens-itive to music after birth. They did differ, however, in their assessment of the benefits of faster development of musical hearing and the positive influence of the mother’s musical activities on the development of musical abilities in the child. The analysis showed that in both cases more women aged 51-70 formulated such opinions. On the other hand, a statistically higher percentage of young mothers (by 24%) found that a positive effect of their musical activity is the occurrence of a child’s post-natal reactions to music known from the fetal period. Only a small number of respondents admitted that they had no knowledge of any benefits of musical activity during

pre-gnancy (younger women – 4%; older women – 10%, χ2 =2.765, df =1 pχ2=0.096).

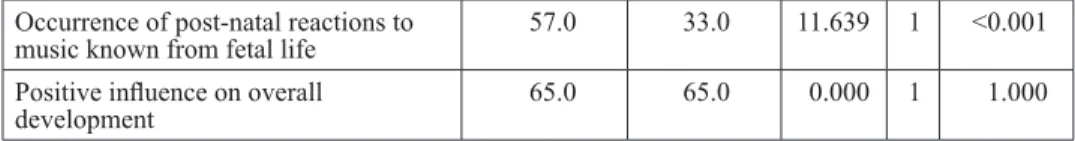

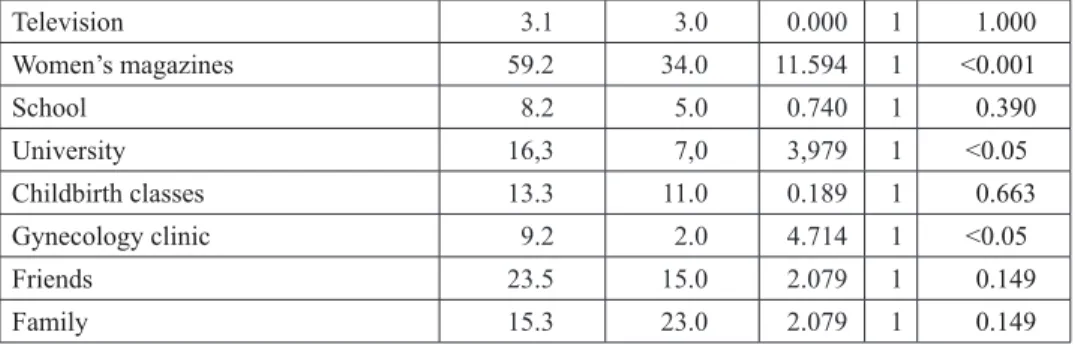

The next step in the study was to determine the sources of women’s knowledge regarding the musical development of children in the prenatal period.

Table 2 Sources of knowledge on a child’s musical development

in the prenatal period

Responses Age 18-35 years N=982 Age 51-70 years N=100 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2 Scientific literature 36.7 18.0 8.219 1 <0.01 The Internet 49.0 13.0 28.895 1 <0.001

10 See: Arya, Chansoria, Konanki &Tiwari, Maternal Music Exposure During Pregnancy Influ¬ences

Neonatal Behaviour: an OpenLabel Randomized Controlled Trial; Partanen, Kujala, Tervaniemi

& Huotilainen, Prenatal Music Exposure Induces LongTerm Neural Effects; Garcia- Gonzales, Ventura-Miranda, Manchon-Garcia, Pallares-Ruiz, Marin-Gascon, Requena-Mullor, Alarcón-Ro-driguez & Parron-Carreño, Effects of Prenatal Music Stimulation on Fetal Cardiac State, New

born and Vital Signs of Pregnant Women: a Randomized Controlled Trial”; Provasi, Anderson,

Television 3.1 3.0 0.000 1 1.000 Women’s magazines 59.2 34.0 11.594 1 <0.001 School 8.2 5.0 0.740 1 0.390 University 16,3 7,0 3,979 1 <0.05 Childbirth classes 13.3 11.0 0.189 1 0.663 Gynecology clinic 9.2 2.0 4.714 1 <0.05 Friends 23.5 15.0 2.079 1 0.149 Family 15.3 23.0 2.079 1 0.149

Source: the author’s own elaboration

Most mothers in both groups acquired their knowledge in this regard from women’s magazines. Nearly half of young women also used the Internet and about 1/3 used scientific literature, and in each of these areas the analysis showed significant differen-ces between both groups. The greatest differendifferen-ces in the results (by 36%) concerned the use of the Internet, which is accounted for on the one hand by the absence of this medium in the years when the majority of the women aged 51-70 became mothers, and on the other hand by the natural ease of use among young people. Statistical-ly, more younger women not only used these sources, but also acquired knowledge about their child’s musical development at the university and at gynecology clinics. This should be combined with a significant increase in the knowledge about human fetal life in recent decades, and with growing popularization of this knowledge. The respondents, however, did not differ in their responses concerning television, school, childbirth classes, friends and family. It was also found that statistically more older women (32%) than younger women (5.1%) admitted that they did not know about a child’s musical development in the prenatal period (χ2 = 24.175; df = 1; pχ2 < 0.001). Further analysis showed that there are no significant differences between the groups in terms of the women’s knowledge of the stage of fetal life when a child starts to hear and react to music.

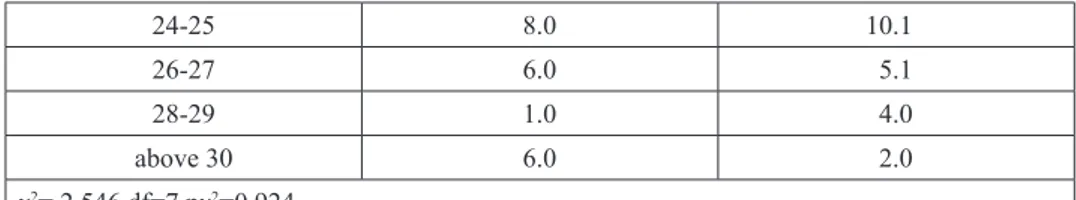

Table 3 The period when children begin to hear and react to sounds

according to the respondent women

Week of fetal life

Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=99 % % 14-17 41.0 38.3 18-19 19.0 16.2 20-21 16.0 16.2 22-23 7.0 8.1

24-25 8.0 10.1

26-27 6.0 5.1

28-29 1.0 4.0

above 30 6.0 2.0

χ2= 2.546 df=7 pχ2=0.924

Source: the author’s own elaboration

Some scientific reports say that human fetuses begin to hear and react to sounds,

including music, between the ages of 24 and 28 weeks11. Other sources report that the

fetus responds to sound stimuli starting in the nineteenth week of pregnancy12. Beliefs

on this subject were also divided among the mothers polled, with the majority of the respondents from both groups indicating the time periods mentioned above. It is also worth noting that approximately 40% of the women in both groups said that these processes started even earlier.

In the subsequent part of the study, the respondents were questioned about the most important stages in the musical development of the child.

Table 4 The most important stages in the musical development of children,

according to the participating women

Developmental period Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=99 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2 Prenatal 31.0 36.0 0.561 1 0.454 Infancy 29.0 21.0 1.707 1 0.191 Post-infancy 11.0 11.0 0.000 1 1.000 Preschool 22.0 27.0 0.960 1 0.327

Young school age: 7-9 years 6.0 5.0 0.096 1 0.756

Young school age: 10-12 years 1.0 0.0 1.005 1 0.316

Source: the author’s own elaboration

Upon analysis, it was found that the largest number of mothers from both groups (over 30%) indicated the prenatal period as most important. Slightly fewer young

11Birnholz, Benacerraf; after: Arya, Chansoria, Konanki &Tiwari, Maternal Music Exposure Dur

ing Pregnancy Influences Neonatal Behaviour: an OpenLabel Randomized Controlled Trial; Ruth Litovsky, „Development of the Auditory System”, Handbook of clinical auditory system 129 (2015).

12 Peter G. Hepper, Sara B. Shahidullah, „Development of Fetal Hearing”, Archives of Disease in

wo men indicated the stages of infancy and pre-school age, but no statistical differen-ces between the group respondents’ belonged to and their answers were found. It is worth noting that the influence of music on the fetus in the prenatal period, as well as the influence of exposure to music in this period on subsequent musical development, is not fully known. However, as already mentioned, existing research indicates the im-portance of fetal life in this respect, although it is not known whether it is as important as the subsequent phase of early childhood13.

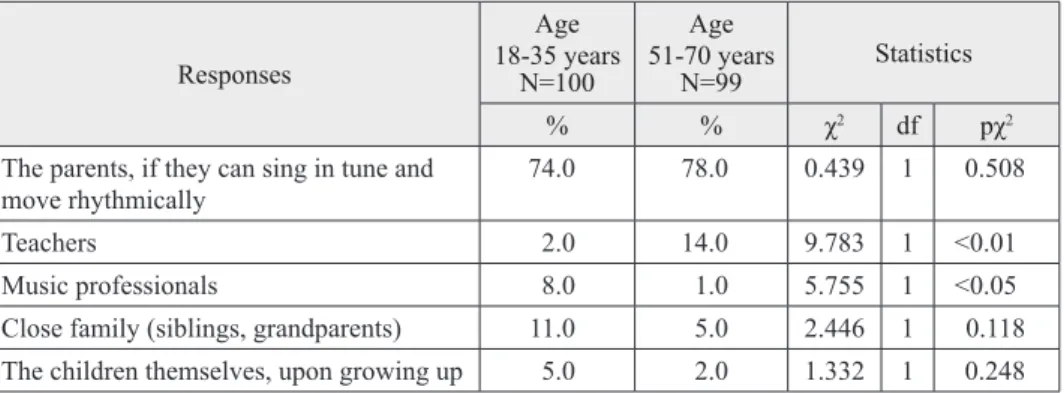

It was also interesting to find out who, according to the women, should initially be responsible for the child’s musical development.

Table 5 People who should first be responsible

for the child’s musical development

Responses Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=99 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2

The parents, if they can sing in tune and

move rhythmically 74.0 78.0 0.439 1 0.508

Teachers 2.0 14.0 9.783 1 <0.01

Music professionals 8.0 1.0 5.755 1 <0.05

Close family (siblings, grandparents) 11.0 5.0 2.446 1 0.118 The children themselves, upon growing up 5.0 2.0 1.332 1 0.248 Source: the author’s own elaboration.

In the view of most mothers, the persons who should be primarily responsible for this aspect of the child’s development are the parents, with the proviso, however, that they can sing in tune and move in time to music. This attitude shows that the women surveyed were aware that the quality of early support for a child’s musical

development also depends on the parents’ necessary predispositions in this regard14.

Further analysis showed statistical differences between the groups, which were rela-ted to indications concerning teachers and music professionals. In the view of several mothers, these people should take care of their child’s musical development from the beginning, in the first case this response was given by more older women, and in the second by more younger women.

13 Beata Bonna, Zdolności i kompetencje uczniów w młodszym wieku szkolnym, 29; see also: David

K. James, C.J. Spenser, B.W. Stepsis, „Fetal Learning: a Prospective Randomized Controlled Study”, Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Ginecology 20, 5 (2002); Provasi, Anderson, Barbu-Roth, Rhythm Perception, Production, and Synchronization During the Perinatal Period.

14Cf. Edwin E. Gordon, Teoria uczenia się muzyki. Niemowlęta i małe dzieci (Gdańsk: Harmonia

Musical activity of women during pregnancy

To find an answer to the second research problem, the respondents were asked whether they undertook musical activity during pregnancy with the awareness of the influence of music on their child. The analyses showed that belonging to a given group highly differentiated the responses of the women (χ2 = 42.593; df=1 pχ2< 0.001). This qu-estion was answered positively by 69% of the younger respondents and 23% of the older respondents, which shows that more women who recently became mothers en-gaged in deliberate musical stimulation.

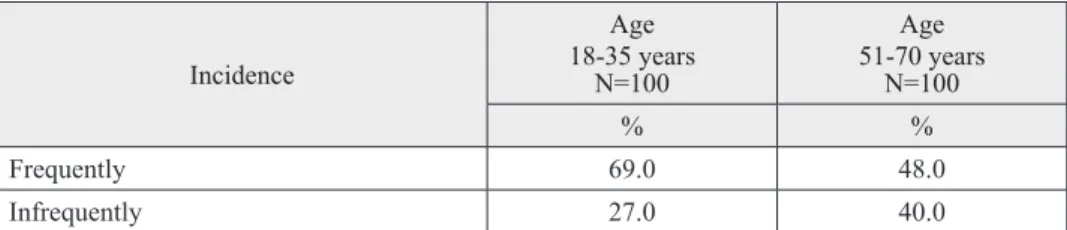

Singing is an enormously important form of early support for human musical de-velopment. The source literature underscores how children in the fetal period show preferences for listening to calm music, with a constant tempo and rhythm close to the heart rate of an adult15. They show a particular preference for lullabies sung by

their mothers, which have a calming effect16. Some researchers believe that singing

by pregnant women has a beneficial effect on the psychological and intellectual deve-lopment of the child, including its musical intelligence17. In infancy, however, singing

also influences the formation of social bonds18. It has also been shown that fetal

mo-vements, which are a reaction to the mother’s singing, contribute not only to motor development but also to the development of psychological functions of the child19.

The analysis of data concerning women’s singing revealed a highly significant difference between the respondent belonging to a specific group and the frequency of this form of musical activity.

Table 6. Incidence of singing Incidence Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=100 % % Frequently 69.0 48.0 Infrequently 27.0 40.0

15 Dorota Kornas-Biela, „Okres prenatalny”, in Psychologia rozwoju człowieka. Charakterystyka

okresów życia człowieka, eds. Barbara Harwas-Napierała, Janusz Trempała (Warszawa:

Wydaw-nictwo Naukowe PWN, 2009), 30.

16 Polverini-Rey; after: Whitwell, The Importance of Prenatal Sound and Music.

17 Clark, Gardner, Ludington-Hoe, Thurman, Langness; after: Maria Manturzewska, Barbara

Ka-mińska, „Rozwój muzyczny człowieka”, in Wybrane zagadnienia z psychologii muzyki, eds. Ma-ria Manturzewska, Halina Kotarska (Warszawa: WSiP), 32; Fridman, The Maternal Womb: the

First Musical School for the Baby, 17; see also: Beata Bonna, „Muzyka w okresie prenatalnym.

Zaangażowanie kobiet w ciąży we wspieranie rozwoju muzycznego dziecka”, in: Historyczne

i współczesne aspekty badań nad kulturą muzyczną i poezją, ed. Beata Bonna (Bydgoszcz:

Byd-goskie Towarzystwo Naukowe, 2012).

18 See: Laura K. Cirelli, Sandra E. Trehub, „Infants Help Singers of Familiar Songs”, Music

& Science 1 (2018).

Never 4.0 12.0 χ2 = 10.292 df =1 pχ2< 0.01

Source: the author’s own elaboration.

Studies have shown that more young mothers (by 21%) often sang during pre-gnancy, while fewer (by 13%) engaged in this activity rarely, or did not sing at all (a difference of 8%). This trend is also confirmed by other reports20.

Further statistical differences were related to the type of songs sung during pre-gnancy, with more young respondents singing lullabies (by 14.1%) and sung poetry (by 12.2%).

Table 7 Types of songs sung

Type Age 18-35 years N=97 Age 51-70 years N=88 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2 Lullabies 50.5 36.4 5.996 1 <0.05 Sung poetry 24.7 12.5 5.853 1 <0.05 Popular 52.6 43.2 3.421 1 0.064 Religious 24.7 39.8 2.909 1 0.088

Songs known from their own childhood 37.1 47.7 0.757 1 0.384 Source: the author’s own elaboration.

It is worth noting that more than half of the young women reached for the reperto-ire of popular songs and lullabies, while women aged 51-70 when they were mothers preferred songs they knew from their own childhood and, as mothers in the other group, popular songs. The trend visible among the young mothers is confirmed by studies conducted by Sirac, which showed that lullabies and popular songs dominated

the repertoire of women expectant mothers21.

The character of the songs sung was also evaluated.

20Cf. Candice Sirac, Mothers’ Singing to Fetuses: The Effect of Music Education (Florida State

University Libraries, Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations, 2012), http://fsu.digital.flvc. org/islandora/object/fsu:183117/datastream/PDF/view; Lori A. Custodero, Pia R. Britto, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, „Musical Lives: a Collective Portrait of American Parents and Their Young Chil-dren”, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 24, 5 (2003).

Table 8 The character of songs sung

Character Age 18-35 years N=97 Age 51-70 years N=88 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2 Calm 64.9 71.6 0.000 1 1.000 Fast 15.5 12.5 0.707 1 0.400 Lively 23.7 10.2 7.292 1 <0.01 Joyful 68.0 59.1 4.051 1 <0.05 Melancholy 16.5 13.6 0.664 1 0.415 Varied in character 18.6 8.0 5.531 1 <0.05

Source: the author’s own elaboration.

It was found that most mothers sang calm and joyful melodies. In the latter case, a significant difference was found between the groups, with slightly more young wo-men (by 8.9%) performing this type of song. Further statistical differences were ob-served in lively songs, as well as songs of varied character, which proved to be more popular among younger mothers.

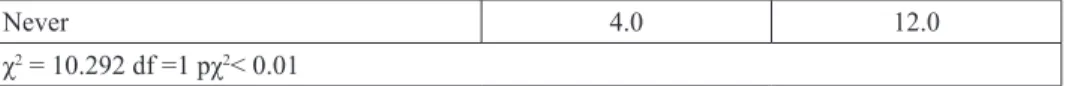

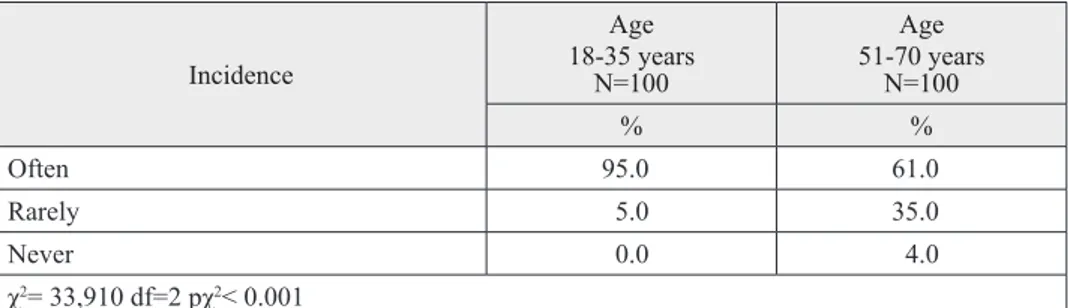

Surrounding a child with music in the prenatal development phase is an impor-tant element of early musical stimulation. The source literature indicates that voice, speech, and music contain various rhythmic components recognized by the fetus and the newborn child. These are the predominant auditory signals in the womb, so they are believed to play a key role in the perception and learning of voice, speech, and

music22. It seemed interesting to find out how often the mothers surveyed not only

engaged in singing, but also listened to music during pregnancy.

Table 9 Incidence of listening to music

Incidence Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=100 % % Often 95.0 61.0 Rarely 5.0 35.0 Never 0.0 4.0 χ2= 33,910 df=2 pχ2< 0.001

Source: the author’s own elaboration

22Provasi, Anderson, Barbu-Roth, Rhythm Perception, Production, and Synchronization During the

The study showed a highly significant difference between the groups. Again, the women who became mothers recently proved to be more active. As many as 95% of them declared that they listened to music frequently, while the others listened to it rarely. In the other group, 34% fewer mothers engaged in such activity frequently, and 30% more engaged in it rarely. Very few women in this group admitted that they did not listen to music at all during pregnancy.

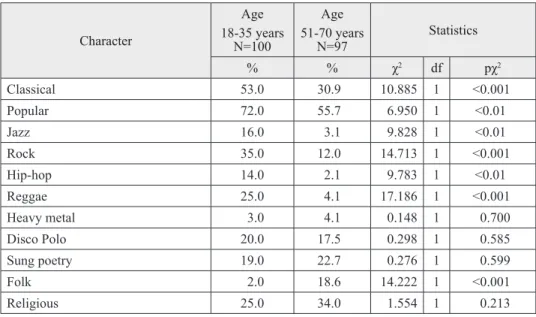

Other highly significant differences were revealed in the women’s responses re-garding genres of music, such as popular, classical, rock, reggae, jazz, hip-hop and folk. Nearly all of these kinds of music, except folk music, was listened to more by the young mothers.

Table 10 Genres of music played

Character Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=97 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2 Classical 53.0 30.9 10.885 1 <0.001 Popular 72.0 55.7 6.950 1 <0.01 Jazz 16.0 3.1 9.828 1 <0.01 Rock 35.0 12.0 14.713 1 <0.001 Hip-hop 14.0 2.1 9.783 1 <0.01 Reggae 25.0 4.1 17.186 1 <0.001 Heavy metal 3.0 4.1 0.148 1 0.700 Disco Polo 20.0 17.5 0.298 1 0.585 Sung poetry 19.0 22.7 0.276 1 0.599 Folk 2.0 18.6 14.222 1 <0.001 Religious 25.0 34.0 1.554 1 0.213

Source: the author’s own elaboration.

The data show that in both groups, the largest number of respondents surrounded their child with popular music during pregnancy. More than half of the young women also listened to classical music. Many of them also reached for rock and reggae songs, as well as religious music, the latter kind also preferred by about 1/3 of women aged 51-70. The least popular among younger mothers turned out to be folk music and, perhaps understandably, heavy metal, which along with other genres, i.e. hip-hop, jazz and reggae, were enjoyed very little by women from the other group.

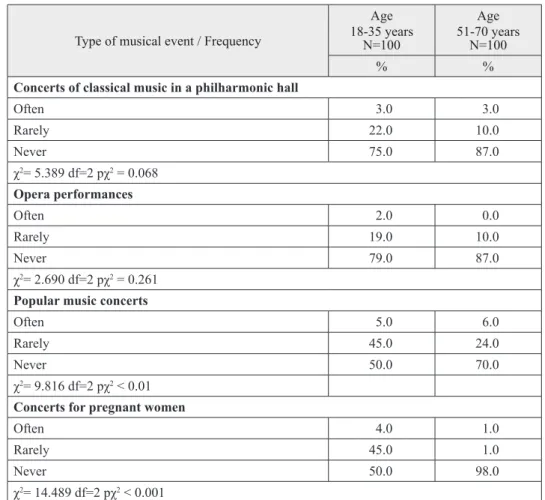

The attendance of pregnant women at musical events during pregnancy was also evaluated.

Table 11 Prevalence of attendance at musical events

Type of musical event / Frequency

Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=100 % %

Concerts of classical music in a philharmonic hall

Often 3.0 3.0 Rarely 22.0 10.0 Never 75.0 87.0 χ2= 5.389 df=2 pχ2 = 0.068 Opera performances Often 2.0 0.0 Rarely 19.0 10.0 Never 79.0 87.0 χ2= 2.690 df=2 pχ2 = 0.261

Popular music concerts

Often 5.0 6.0

Rarely 45.0 24.0

Never 50.0 70.0

χ2= 9.816 df=2 pχ2 < 0.01

Concerts for pregnant women

Often 4.0 1.0

Rarely 45.0 1.0

Never 50.0 98.0

χ2= 14.489 df=2 pχ2 < 0.001

Source: the author’s own elaboration.

The analyses show that attendance at concerts of popular music and concerts for expectant mothers differed statistically between the groups compared. In the first case, 20% more women aged 51-70 did not participate in them, and 21% fewer women at-tended such concerts rarely. A small percentage of the respondents from both groups answered that they often attended such events, or concerts for pregnant women. It was shown that more younger mothers (by 13%) participated in such concerts rarely. It was also found that fewer young women (by16%) did not attend these events at all. This situation can be explained by the lack or low incidence of such events in the years when the older women were new mothers. The study also showed that, apart from the moderate popularity of pop music concerts among the young women, other forms of direct participation in musical culture did not arouse much interest among respondents in either of the groups.

Another form of fostering music appreciation in children from an early age is re-lated to mothers playing an instrument. This entails the possibility of surrounding the fetus with live music performed by the mother, although it does require well develo-ped skills that would ensure the high quality of sound reaching the child. The respon-dents were also asked about the frequency of taking up this form of musical activity.

Table 12 Prevalence of playing a musical instrument

Type of musical event / Frequency

Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=100 % % Often 11.0 9.0 Rarely 14.0 6.0 Never 75.0 85.0 χ2= 4.025 df=2 pχ2 = 0.134

Source: the author’s own elaboration.

The study did not reveal any statistical differences between the groups. It was found that a vast majority of the women did not play an instrument during pregnancy. Only a few of the respondents in both groups played an instrument, be it often or rarely.

Yet another form of musical activity is movement to music, which not only rela-xes the mother and child, but can also support the development of the fetus in many

respects23. It was found that the women did undertake activities involving rhythmic

movement to music, although both groups significantly differed in the frequency of engaging in this type of activity.

Table 13 Movement to the rhythm of music

Frequency Age 18-35 years N=100 Age 51-70 years N=100 % % Often 73.0 38.0 Rarely 24.0 42.0 Never 3.0 20.0 χ2= 28.510 df=2 pχ2 < 0.001

Source: the author’s own elaboration.

23See: Arya, Chansoria, Konanki &Tiwari, Maternal Music Exposure During Pregnancy Influ ences

Neonatal Behaviour: an OpenLabel Randomized Controlled Trial; Provasi, Anderson, Bar-bu-Roth, Rhythm Perception, Production, and Synchronization During the Perinatal Period.

Once again, the young mothers proved to be more active in this regard. The gre a- test percentage difference (35%) was found in those women who engaged in such musical behavior frequently.

The mothers’ observations of their children’s responses to music

The subsequent part of the study was devoted to observations by the women concer-ning their children’s reactions to the music to which they were exposed in the prenatal period. As already mentioned, the source literature indicates that already at the stage of fetal life the child starts to recognize music and becomes used to repetitive sound stimuli, which indicates the occurrence of a simple form of learning24.

Table 14 Children’s reactions to the music

to which they were exposed in the prenatal period

Type of reaction Age 18-35 years N=99 Age 51-70 years N=84 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2 Calmness 46.5 47.6 1.853 1 0.396 Excitation (mobility) 28.3 7.1 17.151 1 <0.001 Kicking 24.2 11.9 6.945 1 <0.01 No reaction 12.1 38.1 11.655 1 <0.001

Source: the author’s own elaboration.

The analysis showed that the largest number of respondents from both groups agreed that the children were calm during exposure to music, which may suggest that the musical works presented in their environment were repeated frequently. In other areas, there were statistical differences between the responses in both groups. It was found that more young women observed a state of excitement in their child (by 21.2%) and felt them kicking (by 12.3%), which could be a reaction to a new stimu lus, in this case to unknown music. On the other hand, a higher percentage of mothers from the opposite group (by 26%) did not notice any reaction by the fetus. It should therefore be recognized that women who had become mothers recently observed their chil-dren more closely, which is probably related to their greater musical activity un der- taken with the awareness of the influence of music on the fetus.

24See: Peter G. Hepper, „An Examination of Fetal Learning Before and After Birth”, Irish Journal

of Psychology 12, 2 (1991); Arya, Chansoria, Konanki & Tiwari, Maternal Music Exposure Dur ing Pregnancy Influences Neonatal Behaviour: an OpenLabel Randomized Controlled Trial.

It is worth noting that earlier research conducted under the direction of the author among expectant mothers showed that children tended to calm down under the influ-ence of music to which they were exposed often, and that this did not occur with music unknown to them. Some mothers also noticed that children made violent and abrupt movements when exposed to loud music, while relaxing music made them calm, and

their movements became calmer25. Other studies show that in the prenatal phase of

development over 30% of fetuses show contrasting reactions to changes in the tempo of the music presented, which may be the earliest manifestation of children’s musical

response in the womb (Shelter 1989; see also Bonna, 2012)26.

Both groups significantly differed in their indications concerning the music

pre-ferred by newborns (χ2=15.230 df=1 pχ2<0.001). The data showed that 67% of the

younger and 39.4% of the older women observed such preferences, but they differed in their assessment of the type of music preferred by the newborns.

Table 15 Types of music preferred by newborn children

Type of music Age 18-35 years N=66 Age 51-70 years N=41 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2 Calm, atmospheric 22.7 61.0 3.125 1 0.077 Lively 36.4 24.4 6.945 1 <0.01

Music to which the child was exposed

often in the prenatal period 45.5 29.5 15.724 1 <0.001 Source: the author’s own elaboration.

Most young women noticed that children at birth preferred music to which they were often exposed to during pregnancy. These observations are confirmed by a study conducted by B.J. Satt, which showed that newborns prefer melodies perfor-med by mothers in the prenatal period to those presented by mothers only after they

were born27. Recognition and preference by newborn babies of melodic sequences

sung many times by their mothers in the last weeks of pregnancy is confirmed by

other studies28. Further analysis showed that about 1/3 of the young mothers noted

25Bonna, Muzyka w okresie prenatalnym. Zaangażowanie kobiet w ciąży we wspieranie rozwoju

muzycznego dziecka; see also: Bonna, Zdolności i kompetencje uczniów w młodszym wieku szkol

nym.

26Donald J. Shelter, „The Inquiry Into Prenatal Experience: a Report of the Eastman Project

1980-1987”, Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health 3 (1989); see also: Bonna, Muzyka w okresie prenatalnym. Zaangażowanie kobiet w ciąży we wspieranie rozwoju muzycz nego dziecka.

27After: Whitwell, The Importance of Prenatal Sound and Music.

28Cooper & Aslin, after: Provasi, Anderson, Barbu-Roth, Rhythm Perception, Production, and Syn

a pre ference for lively music in their children, while women aged 51-70 had fewer

such observations in both cases. The answers provided by the mothers differentiated

the studied groups statistically. Significant differences were not found only in the respon ses concerning the children’s preferences for calm, atmospheric music, which were noted by more than half of the older women.

Subsequent analyses revealed further differentiation in the results of observations related to the reaction of the newborn children to music to which they had been expo-sed in the prenatal period.

Table 16 Types of children’s reactions

to music known from the fetal period

Type of reaction Age 18-35 years N=71 Age 51-70 years N=38 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2

The child became calm 71.8 76.3 10.083 1 <0.001

Seemed to listen closely 57.7 26.3 25.293 1 <0.001

Smiled 43.7 34.2 9.441 1 <0.01

Turned toward the source of the sound 45.1 36.8 9.147 1 <0.01

Became agitated 12.7 13.2 1.229 1 1.229

Became restless 0.0 2.6 1.005 1 1.005

Cried at times 4.2 0.0 3.046 1 3.046

Source: the author’s own elaboration.

More than 70% of the mothers from both groups noticed that their child calmed down on presentation of music known from the prenatal period. This fact is also con-firmed by other reports, which show that children exposed to music during the fetal period are very focused when they hear it at birth, which is attributed to the existence of long-term memory. They also show increased alertness, decreased heart rate, and

reduced mobility29. However, the responses indicating that the children calmed down

varied statistically between the two groups studied, with slightly more women who gave birth long ago (by 4.5%) observing the reaction described above.

Other highly significant differences were found in the observations indicating that the child seemed to be listening, smiling, or turning toward the source of the sound. This time, however, more young women noticed such behaviors. Commenting on the-se results, it can be assumed that the respondents from both groups gathered generally accurate observations on this issue. The descriptions of the children’s reactions to mu-sic known from the fetal period confirm these observations: “I noticed that the crying

29Hepper, An Examination of Fetal Learning Before and After Birth; see also: Arya, Chansoria,

Konanki &Tiwari, Maternal Music Exposure During Pregnancy Influences Neonatal Behaviour: an OpenLabel Randomized Controlled Trial.

child calmed down;” “When I sang my child to sleep, it fell asleep more quickly;” “The child, restless at first, became calm.” Few answers of the respondents indicated

contradictory reactions in the newborn children, such as agitation, anxiety, or crying.

It was also interesting to determine whether the mothers had observed different reactions of the child to their own singing as opposed to the singing of other people. The analysis showed that the respondents agreed (χ2 = 0.546 df=1 pχ2 = 0.460), whi-le 38% of the younger and 33% of the older women noticed such differences in the newborn children’s behavior. Here are some of the mother’s observations: “The child looked at me;” “My singing caused the child to calm down;” “It cried when someone else sang, as if it did not like it;” “It reacted positively only to the voices known from the prenatal period”.

In the last phase of the study, the respondents were asked if they noticed a cor-relation between musical activity during pregnancy and after childbirth and with la-ter musical behavior. As a result of the analyses, a highly significant difference was found between the groups (χ2= 20.501 df=1 pχ2 <0.001), while the vast majority of the younger women (78%) and almost half of the older women (47%) noticed such a relationship.

Further analysis revealed statistical differences between the groups in indications concerning the child’s later musical behaviors, which in the opinion of the mothers resulted from their own musical activity.

Table 17 Later musical behaviors of the children

Type of behavior 70.9Age 18-35 years N=79 Age 51-70 years N=48 Statistics % % χ2 df pχ2

The child sang readily 54.4 77.1 0.750 1 0.386

Demanded to be taught songs 38.0 33.3 5.534 1 <0.05 Created his/her own melodies 44.3 20.8 17.921 1 <0.001

Moved rhythmically 70.9 52.1 19.940 1 <0.001

Created his her/own rhythms 20.3 6.3 9.828 1 <0.01

Liked to dance 67.1 58.3 12.968 1 <0.001

Liked listening to a specific instrument 11.4 8.3 2.057 1 0.152 Liked listening to music 62.0 43.8 17.231 1 <0.001 Gladly watched music programs 40.5 27.1 10.351 1 <0.001 Source: the author’s own elaboration

Again, more young mothers noticed that their children demanded to be taught songs, created their own melodies and rhythms, moved in time to music, liked to dan-ce and listen to music, and enjoyed watching music shows. Describing the musical behavior of their child, the respondents pointed out that: “[the children] liked to fall

asleep listening to lullabies, and in response to the music they heard, they started to move rhythmically and dance;” “(...) learned to play the guitar by themselves;” “(...) later on, willingly participated in various musical events, or were members of a music and dance group;” “(...) to this day, [the child] sings beautifully and likes to dance and listen to music”.

Bibliography:

Al‐Qahtani, Noura H. „Foetal Response to Music and Voice”. ANZJOG 45, 5 (2005): 414-417. Arya, Ravindra. Chansoria, Maya. Konanki, Ramesh. Tiwari, Dileep K. „Maternal Music

Ex-posure During Pregnancy Influences Neonatal Behaviour: an Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial”. International Journal of Pediatrics 2012 (2012), 901812.

Bonna, Beata. „Muzyka w okresie prenatalnym. Zaangażowanie kobiet w ciąży we wspie ranie rozwoju muzycznego dziecka”. In Historyczne i współczesne aspekty badań nad kulturą

muzyczną i poezją, ed. Beata Bonna, 55-67. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo

Nauko-we, 2012.

Bonna, Beata. Zdolności i kompetencje muzyczne uczniów w młodszym wieku szkolnym. Byd-goszcz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego, 2016.

Cirelli, Laura K. & Trehub, Sandra E. „Infants Help Singers of Familiar Songs”. Music & Sci

ence 1 (2018): 1-11.

Custodero, Lori A. Britto, Pia R. & Brooks-Gunn, Jeanne. „Musical Lives: a Collective Por-trait of American Parents and Their Young Children”. Journal of Applied Developmental

Psychology 24, 5 (2003): 553-572.

Fridman, Ruth.„The Maternal Womb: the First Musical School for the Baby”. Journal of

Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health 15, 1 (2000): 23-30.

Garcia-Gonzales, J. Ventura-Miranda, M.I. Manchon-Garcia, F. Pallares-Ruiz, T.I. Marin-Ga-scon, M.L. Requena-Mullor, M. Alarcón-Rodriguez, R. & Parron Carreño, T. „Effects of Prenatal Music Stimulation on Fetal Cardiac State, Newborn and Vital Signs of Pregnant Women: a Randomized Controlled Trial”. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice

27 (2017): 61-67.

Gembris, Heiner. „The Development of Musical Abilities”. In MENC Handbook of Musical

Cognition and Development, ed. Richard Colwell, 124-164. New York: Oxford University

Press, 2006.

Gordon, Edwin E. Teoria uczenia się muzyki. Niemowlęta i małe dzieci. Gdańsk: Harmonia Universalis, 2016.

Hepper, Peter G. „An Examination of Fetal Learning Before and After Birth”. Irish Journal of

Psychology 12, 2 (1991): 95-110.

Hepper, Peter G., Shahidullah, Sara B. „Development of Fetal Hearing”. Archives of Disease

in Childhood 71 (1994): 81-87.

James, David K., Spenser, C.J., Stepsis, B.W. „Fetal Learning: a Prospective Randomized Con-trolled Study”. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Ginecology 20, 5 (2002): 431-438.

Kierzkowski, Michał. Rozwój muzyczny dziecka w wieku przedszkolnym. Uwarunkowania,

dynamika i rola w kształtowaniu sfery psychoruchowej. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Athenae

Gedanenses, 2012.

Klimas-Kuchtowa, Ewa. „Znaczenie rozwoju muzycznego dla przyszłej muzykalności”. In

Człowiek – muzyka – psychologia, eds. Wojciech Jankowski, Barbara Kamińska, Andrzej

Kornas-Biela, Dorota. „Okres prenatalny”. In: Psychologia rozwoju człowieka. Charaktery

styka okresów życia człowieka, eds. Barbara Harwas-Napierała, Janusz Trempała, 17-46. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2009.

Lecanuet, Jean P. Graniere-Deferre, Carolyn, Jacquet Anne-Yvonne & DeCasper, Anthony J. „Fetal Discrimination of Low-Pitched Musical Notes”. Developmental Psychobiology 36, 1 (2000): 29-39.

Ruth, Litovsky. „Development of the Auditory System”. Handbook of clinical auditory system 129 (2015): 55-72.

Manturzewska, Maria & Kamińska, Barbara. „Rozwój muzyczny człowieka”. In: Wybrane

zagadnienia z psychologii muzyki, eds. Maria Manturzewska & Halina Kotarska, 25-49. Warszawa: WSiP, 1990.

Parncutt, Richard. „Prenatal Development”. In The Child as Musican. A Handbook of Musical

Development, ed. Gary E. McPherson, 1-31. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Partanen, Eino, Kujala, Teija Tervaniemi, Mari & Huotilainen, Minna. „Prenatal Music Expo-sure Induces Long-Term Neural Effects”. PLoS ONE 8, 10 (2013): e78946.

Provasi Joëlle, Anderson David I., & Barbu-Roth, Marianne. „Rhythm Perception, Production, and Synchronization During the Perinatal Period”. Frontiers in Psychology 5 (2014): 1048. Shelter, Donald J.„The Inquiry Into Prenatal Experience: a Report of the Eastman Project

1980- 1987”. Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health 3 (1989): 171-189.

Sirac, Candice. Mothers’ Singing to Fetuses: The Effect of Music Education. Florida State Uni-versity Libraries, Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations, (2012). http://fsu.digital. flvc.org/islandora/object/fsu:183117/datastream/PDF/view, dostęp: 12.09.2020.

Whitwell, Giselle E. „The Importance of Prenatal Sound and Music”. Journal of Prenatal and