Heidi Köpp-Junk

ORCID: 0000-0001-8193-1568 Polish Academy of Sciences Warsaw kontakt@heidikoepp.de

The Sound of Ancient Egypt – Acoustics and Volume Measurements

Abstract

In ancient Egypt, performances inside and outside buildings are documented (open air, under canopies, in rooms). The article discusses the different acoustic conditions at the various per-formance venues. Within the scope of experimental music archaeology, the volume of replicas of musical instruments from ancient Egypt and modern equivalents was measured. This tech-nical approach in connection with iconographic, textual, and archaeological evidence provides a valuable, practice-oriented contribution to our knowledge of ancient Egypt and its music archaeology.

Keywords:

Music in ancient Egypt, instruments, acoustics, music archaeology, temple, tomb, volume of instruments in decibels (dB)

Introduction

Numerous Egyptian temples and tombs showing musical scenes are still preserved up

to the roof. In addition, several instruments have been found, which allow reliable

re-plicas to be made. Thus the starting point for the investigation of sound and acoustics

in Pharaonic Egypt is relatively good

1. Various studies have been carried out in other

parts of the world to analyze the sound in large caves and further localities

2. Sound

archae ology and acoustics are fields of research that have not previously been

investigated

in Egyptology as intensively as in this analysis. The following study

1 I am grateful to the editor Jarosław Chaciński for the opportunity to present the results of my research in this volume. Moreover, I would like to thank Manon Schutz, Departmental Lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Oxford, for reading a previous version of this article.2 See e.g. Rupert Till, “Sound Archaeology: A Study of the Acoustics of Three World Heritage Sites, Spanish Prehistoric Painted Caves, Stonehenge, and Paphos Theatre”. Acoustics 1, 3 (2019), 661-692, in detail on the various methods and their practicability see ibidem, 662-665.

Vol. 9 pp. 13-33 2020

ISSN 2083-1226 https://doi.org/10.34858/AIC.9.2020.327

© Copyright by Institute of Music of the Pomeranian University in Słupsk Received: 21.09.2020

Accepted: 26.11.2020

focusses on the rela tion of sounds and acoustics, instruments and musical activities

like hand clapping and singing, and the localities where the musical performances

took place, emphasizing the practical aspects. Iconographical and archaeological

evi-dence as well as written sour ces were analyzed. Apart from the combination of texts,

archaeology, and iconograp hy, the innovative aspect lies in joining them with

tech-nical analysis methods

3that have already been used successfully in other contexts

4.

All these aspects were combined to answer the following question: What can we say

today about sound and acoustics based on what has been handed down to us from

ancient Egypt?

The period covered by this analysis is the time from the 5

thmillennium BC, when

the first instruments were attested in ancient Egypt, up to Greco-Roman Times in the

4

thcentury AD.

Sources

For the following, texts as well as iconographical and archeological evidence from

ancient Egypt were analyzed

5. Several texts mention the performing of music, be it

in literary texts or wisdom texts

6or in those accompanying musical scenes

7. Furt h-

ermore, some texts describe a special musical action, as in the temple of Edfu,

mentioning a stage direction with a recitation being accompanied by round frame

3 The author holds a PhD in Egyptology, she is a music archaeologist and practicing musician witha classical trained voice and technical knowhow, i.e. technical experience in terms of room acous-tics (concert halls, churches, monasteries, etc.) and open air stages, years of studio experience, own recordings with Egyptian texts and replicas of instruments from that time, and experience in sound engineering, using her own public address system for live performances. Therefore, the article com-bines Egyptology (textual, iconographical, and archaeological sources) and music archaeology with modern sound technology and analysis methods in form of volume measurements.

4 Ibidem; Rupert Till, “Songs of the Stones: An Investigation into the Acoutisc Culture of Stone henge”,

Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music 1(2) (2010), 1-18; Beate Maria Pomberger, Jörg Helmut Mühlhans. „Der Kreisgraben – ein neolithischer Kon zertsaal?”. Archäologie Österreichs 26/2 (2015), 18-28. Beate Maria Pomberger, Jörg Helmut Mühlhans, Christoph Reuter. “Forschungen zur Akustik der Prähistorie. Versuch einer raum- und instrumente-nakustischen Analys prähistorischer Bauten und Instrumente”, Archaeologia Austri aca 97/98 (2013- -2014), 97-114; Paolo Debertolis, Niccolò Bisconti, “Archaeoacustics Analysis and Ceremonial Customs in an Ancient Hypogeum”, Sociology Study 2 (10) (2013), 803-814; Margarita Diaz-An-dreu, Carlos Garcia Benito, “Acoustic Rock Art Landscapes: A Comparison between the Acoustics of three Levantine Rock Art Areas I Mediterranean Spain”. Rock Art Re search 32 (1) (2015), 46-62. 5 This is not the place for a detailed source criticism of the different sources that will be mentioned

in the following. Of course, the question arises whether a depiction in a temple or tomb is to be accepted at face value or only as a fictional representation. For a complete compilation of the evi- dence from the 5th millennium up to the middle of the 3rd millennium see Heidi Köpp-Junk, Die Anfänge der Musik im Alten Ägypten vom 5. Jt. v. Chr. bis zur 4. Dynastie, passim.

6 Sinuhe, B 68; Papyrus Westcar 10, 3-5; The Instructions of Amenemope; Miriam Lichtheim, An cient

Egyptian Literature II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 149.

7 See e.g. Elmar Edel, „Das Akazienhaus und seine Rolle in den Begräbnisriten“, Münchner Ägypto logische Studien 24 (Berlin: B. Hessling, 1970), fig. 1 (tomb of Debeheni, Giza, LG 90, Dynasty 4).

drums

8. Moreover, there is iconographic evidence: In the 4

thmillennium BC the

ear-liest musical scenes appear on vessels

9, since the 4

thDynasty (ca. 2600 BC) they are

depicted in tombs

10. Furthermore, reliefs in temples, such as in Philae, Dendera, and

Athribis, show musical activities

11. Referring to the archaeological context, in struments

were found, and from time to time they are attested in a special context that enlightens

their use in a specific situation and localization. One such example is a rectan gular frame

drum that was discovered in the nearest surrounding of the tomb of Hat nefer

12,

suggest-ing that the instrument was played at that location dursuggest-ing the funeral.

Music in Ancient Egypt – an Overview

In order not to go beyond the scope of the article, the instruments used in Egypt

are briefly described in the following

13. Membranophones have been

docu-mented since the reign of King Khufu in the middle of the 3

rdmillennium BC

14.

Various types such as the barrel drum

15or the round

16and rectangu lar frame

8 Sylvie Cauville, Didier Devauchelle, Le Temple d’Edfou I (Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéolo gieOrientale, 1984), 209; Dieter Kurth, Treffpunkt der Götter. Inschriften aus dem Tempel des Horus von Edfu (Zürich, München: Artemis-Verlag, 1994), 105.

9 See e.g. British Museum London, inv. no. EA 35502; British Museum London, EA 50751; Bal las, tomb Q593; Köpp-Junk, Die Anfänge der Musik im Alten Ägypten, 52-64.

10Ibidem, 416-418 (tomb of Debeheni, Giza, G 8090, LG 90, Dynasty 4; tomb of Kaikhenet and Ifi, Hemamieh, Dynasty 4; tomb of Nunetjer, Giza, Dynasty 4-6); Richard Parkinson, Reading Ancient Egyptian Poetry among other Histories (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), 14, fig. 1.4 (tomb of Sarenput I, Qubbet el-Hawa, Dynasty 12, 1950 BC); Richard Parkinson, The Painted

TombChapel of Nebamun. Masterpieces of Ancient Egyptian Art in the British Museum

(Lon-don: British Museum Press, 2008), 70, 72-73, 79, fig. 81, 83, 88 (tomb of Nebamun, Thebes, TT 17, Dynasty 18; British Museum London, inv. no. 37981).

11Heidi Köpp-Junk, “Sound of Silence? Neueste Ergebnisse aus der Musikarchäologie”, In Pérégri

nations avec Erhart Graefe. Festschrift zu seinem 75. Geburtstag, eds. Anke Blöbaum, Marianne

Eaton-Krauss, Annik Wüthrich, 267-283. Ägypten und Altes Testament 87, Münster: Zaphon, 2018, 272-273.

12Tomb of Hatnefer and Ramose, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, below TT 71, 18th Dynasty; Egyptian Mu-seum Cairo, CG 69355; Hans Hickmann, Instruments de musique: Nos. 6920169852. Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire. Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale: Cairo 1949, pl. 79.

13En detail see Hans Hickmann, Ägypten. Musik des Altertums II (Leipzig: Deutscher Verlag für Musik, 1961), for the first appearance of the individual instruments used in Egypt see Köpp-Junk,

Die Anfänge der Musik im Alten Ägypten.

14The oldest scene showing a drum is depicted in the tomb of Ifi in Hemamieh near Assiut; Henry George Fischer, Egyptian Women of the Old Kingdom and the Heracleopolitan Period (New York 2000), fig. 13.

15Three examples are now in the Egyptian Museum Cairo (CG 69350, CG 69353, CG 69354; Hick-mann, Instruments de musique, pl. 71-78).

16Egyptian Museum Cairo, JE 4872; Hickmann, Ägypten, 56, fig. 32; Alexandra von Lieven. “Mu-sical notation in Roman Period Egypt”. In Archäologie früher Klangerzeugung und Tonordnung, eds. Ellen Hickmann, Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, Ricardo Eichmann, 497-510. Studien zur Musik-archäologie III, Orient-Archäologie 10 (Rahden, Westfalen: Leidorf, 2002), fig. 1.

drum

17are attested, the latter being largely limited to the 18

thDynasty

(1550-1292

BC)

18. Idiophones are documented in the form of rattles, sistra, me nits, clappers,

bells, and cymbals. Rattles are known to have been used since the 5

thmillennium

BC; they are the oldest instruments in Egypt

19. Clappers first appe ared in the

4

thmillennium as paintings on vessels

20, and since 3000 BC as in struments. The latter

often have the shape of hands, decorated with the face of the goddess Hathor

21.

The sistrum is documented since the 4

thDynasty (2604-2504 BC)

22, and the menit

since the 6

thDynasty (2347-2216 BC)

23. Bells and cymbals have been

archaeolo-gically handed down from the Greco-Roman period in particu lar

24, while textual

evidence may have existed as early as 2100 BC

25. In religious setting, idiophones

and membranophones were preferred; especially sistra, me nits, and round frame

drums appear in this context

26. Egyptian aerophones are flu tes, isolated vessel

flu-tes, and forerunners of the modern clarinet, oboe, and trum pet. The trumpets were

not played with a mouthpiece like nowadays and they were made of metal. Two

trumpets of this kind, one of silver and one of bronze, were found in the tomb

of Tutankha mun

27. Referring to oboes and clarinets it should be stated that

17See e.g. Egyptian Museum Cairo, CG 69355; Hickmann, Instruments de musique, pl. 79. 18Hans Hickmann, “Le tambourin rectangulaire du Nouvel Empire. Miscellanea Musicologica X”,

Annales du Service des antiquités de l’Égypte (1951): 317-333.

19Clay rattle from Merimde (4600-4100 BC, Egyptian Museum Cairo, CG 69721); Hickmann,

Instruments de musique, 74.

20On a vessel from Naqada II (ca. 3300 BC) now in the Museum August Kestner in Hannover, inv.--no. 1954.125 men playing clappers are depicted, for a similar scene see a vessel from el-Amrah (British Museum London, EA 35502, Nagada II).

21See e.g. Roemer- and Pelizaeus-Museum Hildesheim, New Kingdom, inv. no. 5523 (provenance unknown); Arne Eggebrecht. Ägyptens Aufstieg zur Weltmacht (Mainz: von Zabern, 1987), no. 97. 22The earliest evidence of sistra can be found on the relief from the tomb of Nunetjer in Giza.

It is dated to Dynasty 4 or 5, but sometimes even to Dynasty 6 (Dorothea Arnold, When the

Pyramids were built (New York: Rizzoli, 1999), 303; PM III, 217; Monika Schuol,

“Hethitis-che Kultmusik”, OrientArchäologie 14 (Rahden, Westfalen: Leidorf, 2004), 80, pl. 21, fig. 57.1; “The Giza Archives”, accessed September 08, 2020, http://www.gizapyra mids.org/view/ sites/asitem/search@/0?t:state:flow=9872093a-fe93-4c2b-b47c-81280e1dac0b)). Since Dy-nasty 6 at the latest, the number of documents has been increasing, as shown for ex ample by a sistrum from Assiut (British Museum London, EA 47542).

23 Elisabeth Staehelin, „Untersuchungen zur aegyptischen Tracht im Alten Reich“, Münchner Ägyp tologische Studien 8 (Berlin: Hessling, 1966), 125-126, pl. 10, 13, fig. 15, 19.

24See the cymbal from the Roman Period, today in the Petrie Museum London (UC 33268) and the bells in the same museum (UC 30361, 30362). The earliest bells date to the New Kingdom (Museum of Fine Art Boston, inv. no. 11.3074, “MFA Museum of Fine Arts Boston”, acces-sed August 13, 2020, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/139918/bell?ctx=b5a1971c-3a33-4474-b7b7-fbf89a67f0e4&idx=0), but the evidence is still rare in this phase as well as in the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Period.

25 Coffin Texts CT I 74 e-g, CT I 248 b-c; von Lieven, Osirisliturgie, 27, she points out that the form of the metal instrument referred to therein is not entirely clear.

26Heidi Köpp-Junk, “Göttliche Klänge. Zur manipulativen Kraft der Musik im Alten Ägypten”, In

Die geistige Macht der Musik, ed. Jean Ehret, Luxemburg; Heidi Köpp-Junk, “Rasseln für die

Ewigkeit: Die ältesten Perkussionsinstrumente des Alten Ägypten“, In Ancient Percussion Instru ments: Organology Perceptions Multifunctionality, ed. Arnaud Saura-Ziegelmeyer.

27Tomb of Tutankhamun, Thebes, KV 62, 18th Dynasty; Egyptian Museum Cairo, JE 62007 = CG

69850 (trumpet made of silver), JE 62008 = CG 69851 (trumpet made of bronze); Hickmann, Instruments de musique, pl. 87-90.

no mouthpiece from ancient Egypt survived, but some wind instruments of

pha-raonic times “resem ble modern folk clarinets with one lamella, and therefore are

called ‘clarinets’”

28. The same applies to a double lamella instrument, resembling

the Greek Aulos

29.

The earliest flute is attested ca. 3100 BC

30, the clarinet since the 5

thDynasty

(ca. 2500 BC)

31, the oboe and the trumpet since the 18

thDynasty (ca. 1480 BC)

32.

Chordophones are represented by harp, lyre, and lute. The former have been

do-cumented in various forms since the 4

thDynasty in the reign of Pharaoh Khufu

(2604-

-2581 BC)

33.

The oldest representation of a lyre dates from the Middle King dom

(abo-ut 1900 BC)

34, while lutes have been documented in Egypt since the Se cond

Interme-diate Period (ca. 1550 BC)

35. Hand clapping is attested since Dynasty 0 in the reign of

the ruler Scorpion II (ca. 3100 BC)

36, singing on the stela of Mer ka from Dynasty 1

(ca. 2853-2828 BC)

37. Nevertheless, hand clapping, just like singing and dancing,

is one of the earliest musical activities, so it was certainly practiced earlier.

Music played a very important role in ancient Egypt since the earliest times; as

mentioned above, the oldest instrument, i.e. a rattle, dates to the 5

thmillennium BC

38.

Since then, they appear in tombs, sanctuaries, temples, and settlements. In the 4

thmillennium BC clappers, painted on vessels, were given into the tombs, so that the

deceased could use them to contact the gods to support them on their way to the

netherworld

39. Since the 4

thDynasty (ca. 2600 BC), music scenes were a very popular

topic in the wall reliefs and paintings of tombs.

28 Bo Lawergren, “Music”.In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt 2, ed. Donald. B. Red ford, 450-454 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 450.

29Ibidem.

30A flute player is depicted on the so-called Two-Dogs Palette (Hierakonpolis, main deposit; Ash-molean Museum Oxford, E 3924; James Edward Quibell. Hierakonpolis II. Egyptian Research Account Memoir 5 (London: Quaritch, 1902), pl. 28.

31See e.g. Egyptian Museum Cairo, JE 28504 = 1533; Saleh, Sourouzian, Hauptwerke, Nr. 61. 32 For an oboe see the painting in the tomb of Aametju, called Akhmose, Thebes, TT 84, 18th

Dyna-sty; Lise Manniche, Ancient Egyptian Musical Instruments. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien 34 (München: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1975), pl. 5, fig. 10. For the trumpet see the one in the tomb of Akhmose in Amarna (tomb no. 3, 18thDynasty; Hans Hickmann, “La trompette dans l’Égypte

ancienne”, Supplément aux Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 1 (Kairo 1946), fig. 5). 33Tomb of Kaikhenet and Ifi in Hemamieh and the one of Kaemnefer in Hagarseh (Köpp-Junk, Die

Anfänge der Musik, 246-248, fig. 116-117).

34 A wall painting in the tomb of Khnumhotep from Dynasty 12 shows a lyre within a scene depict-ing an Asian caravan (Percy Edward Newberry, Beni Hasan I. London: Archaeological Survey of Egypt, 1893, pl. 31). Although this does not imply that the lyre came to Egypt in exactly this way, the illustration shows that it was per se known at that time.

35Köpp-Junk, “Sound of Silence”, 270.

36Mace head of Scorpion II, Hierakonpolis, main deposit, Dynasty 0; Ashmolean Museum Oxford, E 3632; James Edward Quibell, Hierakonpolis I. Egyptian Research Account Memoir 4 (Lon don: Quaritch, 1900), pl. 26c.

37Stela of Merka, Saqqara, mastaba 3505, Dynasty 1; Egyptian Museum Cairo, without number; Walter Bryan Emery. Great Tombs of the First Dynasty III. Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Society 47 (London: Egypt Exploration Society, 1958), 31, pl. 23a-b, 39.

38In detail Köpp-Junk, Die Anfänge der Musik im Alten Ägypten. 39Ibidem, 28-98; Köpp-Junk, “Göttliche Klänge”.

Publication

s referring to the music of ancient Egypt were published since the

ear ly

20

thcentury, with Curt Sachs being one of the earliest researchers in this area

40,

suc-ceeded in the middle of the

20

thcentury

by Hans Hickmann, who wrote numerous

books and artic les on specific topics

41; various other scholars followed in their

foot-steps

42. Yet, acoustic aspects were discussed referring to other cultures

43or to Nubia

44,

but not concerning pharao nic Egypt in the same ways as it is intended in this analysis.

While soundscapes are debated from time to time

45, this takes place in a very

theo-retical way, referring e.g. to textual evidence in ancient Egyptian religious literature

(“the lord with the roaring voice is pleased”)

46. In contrast, this article will not focus

on sound experiences in a figurative sense but instead has its emphasis on practice.

This approach, including the connec tion of modern acoustics experience and

measu-ring methods, music archaeology, and Egyptology, is interdisciplinary in nature and

has not been pursued in the same way before in relation to ancient Egypt as it is in

this article.

The combination of these disciplines allows a more profound insight into

40The publication of Sachs, Altägyptische Musikinstrumente, was published 1920, see as well Sachs, Curt. Die Musikinstrumente des Alten Ägypten. Mitteilungen aus der Ägyptischen Samm-lung 3 (Berlin: Curtius, 1921).41Hickmann, Instruments de musique; Hans Hickmann, „Die Gefäßtrommeln der Ägypter“. Mittei

lungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 14 (1956): 76-69; Hickmann, Ägypten, see as well the listing below and many other publications of him.

42See e.g. Manniche, Ancient Egyptian Musical Instruments; Lise Manniche, Music and Musicians

in Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1991); Robert Anderson, Catalogue of An tiquities in the British Museum III: Musical Instru ments (London: British Museum Press, 1976);

Christiane Ziegler, Catalogue des instruments de musique égyptiens. Musée du Louvre, Départ ement des Antiquités Egyptiennes (Paris: Réu nion des Musées Nationaux, 1979); Manfred Bietak, “Eine „Rhythmusgruppe” aus dem späten Mittleren Reich”, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Ar

chäologischen Institutes 56 (1985): 3-18; Alexandra von Lieven, “Eine punktierte Osirisliturgie

(pCarlsberg 589 + PSI inv. I 104 + pBerlin 29022)”. In Hieratic Texts from the Collection, ed. Kim Ryholt, 9-38. The Carlsberg Papyri 7, Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications 30 (Kopenhagen, 2006).

43Pomberger et al., „Der Kreisgraben“, 18-28.

44Cornelia Kleinitz, Rupert Till, Brenda Baker, “The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Ar-chaeology and acoustics of rock gongs in the ASU BONE concession above the Fourth Nile Cataract, Sudan: a preliminary report”. Sudan & Nubia 19 (2015), 106-114; Cornelia Kleinitz, “Soundscapes of the Nile valley: ‘Rock music’ in the Fourth Cataract region”. In Challenges and

Aims in Music Archaeology, eds. Arnd Adje Both, Ricardo Eichmann, Ellen Hickmann,

Lars--Christian Koch, 131-146. Studies in Music Archaeology VI (Rahden Westfalen: Leidorf, 2008); Cornelia Kleinitz. “Acoustic Elements of (pre)historic Rock Art Landscapes at the Fourth Cata-ract”. PAM Supplement Series 2.2/1 (Warsaw 2010), 149-160.

45Colleen Manassa, “Sounds of the Netherworld”, In Mythos und Ritual. Festschrift für Jan Ass

mann zum 70. Geburtstag, eds. Benedikt Rothöhler, Alexander Manisali, 109-135 (Münster: LIT

Verlag, 2008); Colleen Manassa. “Soundscapes in Ancient Egyptian Literature and Religion”. In

Laut und Leise: Der Gebrauch von Stimme und Klang in historischen Kulturen, ed. Erika

Meyer--Dietrich, 147-172 (Bielefeld: transcript-Verlag, 2011); Erika MeyerMeyer--Dietrich, Auditive Räume

des alten Ägypten: Die Umgestaltung einer Hörkultur in der Amarnazeit (Leiden, Bos ton: Brill,

2018); Sibylle Emerit, Dorothée Elwart. “Sound Studies and Visual Studies applied to Ancient Egypt”. In Sounding Sensory Profiles in the Ancient Near East, eds. Annette Schel lenberg, Tho-mas Krüger, 315-334 (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2019); Alexandra von Lieven, “Sounds of Power: The Concept of Sound in Ancient Egyptian Religion”. In Religion für die Sinne, eds. Philipp Reichling, Meret Strothmann, 25-35. Artificium 58 (Oberhausen: Athena, 2016).

the practical side of music in ancient Egypt than only through research on individual

instruments or instrument groups, which is often the focus of other research.

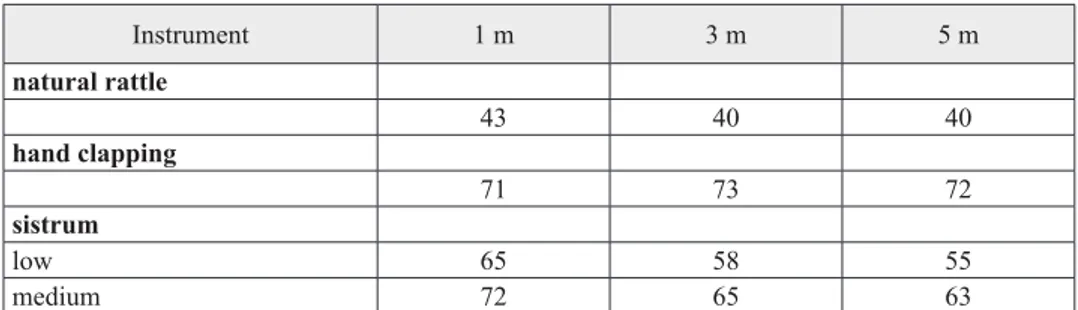

Moreo-ver, due to the modern decibel measurements (Tab. 1), it allows a unique link between

ancient Egypt and today, past and present.

Sound and Acoustics

In order to understand acoustics in rooms, the following will briefly discuss aco ustics

in churches and other performance locations.

The sound checks before live concerts

show that each location has completely different acoustics per se, which further de-

ends on whether it is filled with an audience or whether it is empty

47. The same

applies to full or empty churches, the acoustic features even change based on whether

there are seat cushions or not

48. “The area with pulpit and altar has a much longer

re-verberation than the main room occupied by the church visitors, so that the language

reverberates noticeably when it is heard by the visitors”

49. On the edge between the

sanctuary and the main room, as well as from the gallery, solo singing unfolds well.

But no matter where an unamplified guitar is played inside a church, its sound is

usu-ally lost

50. Chur ches are unsuitable for modern bands with drum and percussion,

play-ing with a public address system, microphones, guitar, and bass amplifiers, because of

the long reverb. While unamplified music and choirs benefit from the reverberation,

it has a negative effect on speech intelligibility, which is why the liturgy was sung.

In churches, the positioning of the pulpit is certainly for acoustic reasons. Furt h-

ermore, for unamplified speech without a microphone,

it is equipped with a so und

cover which limits the sound emission

upwards, as well as with a rear panel for the

same purpose

51.

The unusual acoustics with the long reverberation allows the sacred space to

ap-pear in a special transcendent atmosphere, which has a certain effect on the audience,

and the same applies to ancient Egypt: The monumentality of the buildings

emphasi-zed that these temples and palaces were “not of this world” but belonged to the sphere

of the gods and the pharaohs descending from them

52. Special features of the aco us-

tics, such as a longer reverberation or a particular change in volume, also triggered

special emotions in the listener, not to mention the impression that the sound produced

by the priest and musicians are part of the supernatural realm.

47The author’s own observation.

48 Kurt Eggenschwiler, Karl Baschnagel, Aktuelle Aspekte der Kirchenakustik. Dübendorf: Eigen-verlag, o.J., 1-2, fig. 2. In detail see Jürgen Meyer. Kirchenakustik. Fachbuchreihe Das Musikin-strument (Frankfurt am Main: PPVMedien, 2003), passim.

49Meyer, Kirchenakustik, 220, translation by the author. 50The author’s own observation and experience.

51Hermann Backhaus, J. Friese, E.M. v. Hornbostel, Alfred Kalähne, H. Lichte, E. Lübcke, Er win Meyer, Eugen Michel, Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, H. Sell, Ferdinand Trendelenburg, Hand

buch der Physik VIII, Akustik (Berlin: Springer, 1927/2012), 689.

52Heidi Köpp, “Ägypten und die 10 Gebote heute: Hollywoods Bild von Ägypten im Spiegel der modernen Forschung”. In Verschlungene Pfade. Neuzeitliche Wege zur Antike, ed. Rainer Wie-gels, 203-216 (Rahden, Westfalen: Leidorf, 2011), 215.

Regarding practical aspects, the acoustic conditions during a concert should not be

underestimated. Apart from the room acoustics, two other items referring to sound and

acoustics must be taken into account: Noises are created by the musicians, dancers,

and audience, and moreover, sound is absorbed by them. Musical performances often

take place during banquets. Different ensembles are attested in ancient Egypt; one of

the largest with 29 persons appears in the tomb of Iimery in Giza

53. No drums or

clap-pers are shown, but four people clapping their hands are depicted. As well as the

mu-sic, noises arise from the rustling of the clothes and the necklaces of the musicians, the

barefoot dancers, and the sounds that the audience produces. If the performance took

place during a banquet, people would have been talking and eating, which produces

a background noise.

Moreover, the sound is absorbed by the clothing of the people attending the event,

be it as guests or musicians. All these aspects have an effect on sound and acoustics

within this situation, and the question arises of how music and singing can be asserted

acoustically against these features.

The musical performances attested in ancient Egypt took place in rooms, the open

air, or under canopies

54, as will be shown in the following, and this of course plays

a decisive role concerning acoustics. The sound distribution in an open-air concert

differs from that within a closed room. Moreover, enclosures without a roof show

dif-ferent acoustics than open air venues.

It can be assumed that the phenomenon of sound

and acoustics was also known in ancient Egypt and that musical performances took

place at certain places within a temple or a locality, where the acoustics were optimal.

Nevertheless, it should be considered whether the acoustic features were intended or

just a side effect

55, and that they were only one aspect among others for the selection

of a site for ritual use.

Indoor Music

In closed rooms, the sound distribution and the acoustics are better, making it

ea-sier for the musician to play in front of a large audience. The architectural acoustics

in private homes were different from those in Egyptian rock tombs, funerary

cha-pels, funerary en closures, or temples. The earliest Egyptian temple architecture of

the 4

thmillennium BC is not uniform, but diverse, so that a basic scheme is not (yet)

recognizable, while the mortuary temples of the 4

thDynasty (ca. 2600 BC) already

show a sophisticated con cept

56. It would be very tempting to assume that the change

of the temple architecture is connected to the development of religious practices,

with music being a very important part of it. But of course, this aspect is only one

among many others.

53Iimerj, Giza, G 6020=LG 16, Dynasty 5, ca. 2450 BC; LD II, Blatt 52.

54The exact place of performance is sometimes not clearly identifiable, if no furniture, canopies, or architectural references are depicted in the scenes.

55Jerry Moore, “Set the wild echoes flying”, Antiquity 81 (2007): 795.

56Heidi Köpp-Junk, “Ägyptische Religion – Götter, Tempel und deren Ursprung”. In Von den Ufern

In a text in the temple of Edfu from the Greco-Roman period, built between 237

and 57 BC, a “stage direction”

57is given, with recitations and exclamations of priests

and wailing women musically supported by round frame drums. The room in which

the description appears is dedicated to the Khoiak rites, which were accompanied by

music

58. The room with the inscription has a roof

59; therefore, the acoustic features are

different to musical activities that occured in the open air.

Music was not only played in temples, but also in private houses.

In the tomb of

Mereruka in Saqqara from the 6

thDynasty (ca. 2300 BC), a woman sitting on a bed

plays the harp for her husband

60, and a similar scene is depicted in the tomb of Pepi

at Meir

61. The fact that they sit on a bed suggests that they played the music indoors.

Open-air Music

Several kinds of open-air performances are attested in ancient Egypt. One is

docu-mented as taking place in front of a tomb, others on boats or under canopies.

The earliest musical scenes appear on vessels of the Naqada II period, dating to the

4

thmillennium. They show open-air music in the form of men playing clappers, often

connected to representations of boats

62.

A scene in the tomb of Kaikhenet and Ifi in

Hemamieh (ca. 2600 BC) depicts the drum player Meri performing on a boat as well

63.

In the tomb of Nekhebu at Giza (ca. 2250 BC), a solo harpist is shown, playing again

on a boat in front of a male listener, while both are sitting under a canopy

64. Maybe

these later reliefs refer back to the earliest scenes mentioned above.

An unusual example of a musical scene is depicted in the tomb of Debeheni in

Giza, dating back to the 4

thDynasty (2604-2504 BC)

65. It does not represent the

typical ensembles of this time, which give the impression that entertainment music is

performed like in the boat scenes from the 4

thDynasty mentioned above and others

57Nordwestern corner of the temple of Edfu, room H; Cauville, Devauchelle, Le Temple d’Edfou I, 209, line 7; Kurth, Treffpunkt der Götter, 105; Hickmann, Ägypten, 10.

58Louis Boctor Mikhail, Dramatic Aspects of the Osirian Khoiak Festival (Uppsala: Institute of Egyptology, Uppsala University, 1983), 51-53. In detail see Émile Chassinat, Le mystère d’Osiris

au mois de Khoiak (Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1966-1968).

59 For the localization of the text within the temple and the architecture of room G and H my thanks go to Dr Susanne Woodhouse, Edfu Project, Academy of Science Göttingen/Griffith Librarian for Egyptology and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the University of Oxford’s Sackler Library. 60Prentice Duell, “The Mastaba of Mereruka I: Chambers A 1-10”. Oriental Institute Publications

31 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1938), pl. 94-95.

61Tomb chapel D, No. 1; Aylward Manley Blackman. The Rock Tombs of Meir Part V. Archaeo logical Survey of Egypt 28 (London: Egypt Exploration Society, 1953), pl. 45; Fischer, Egyptian Women, fig. 8. 62Museum August Kestner Hannover, inv.-no. 1954.125; vessel from el-Amrah, British Museum

London, EA 35502, Nagada II; Köpp-Junk, “Musik im Alten Ägypten”, fig. 6.

63 Tomb of Kaikhenet and Ifi in Hemamieh, Dynasty 4. On the question of the gender of the person playing the drum, see von Lieven, Osirisliturgie, 36, note 189; von Lieven, Social Standing, 356. She assumes that it is a male musician.

64Tomb of Nekhebu, Giza, G 2381, 6th Dynasty; PM III, 89-91, Fischer, Egyptian Women, 15, fig. 15. 65Tomb of Debeheni, Giza, G 8090, LG 90; Köpp-Junk, Die Anfänge der Musik im Alten Ägypten, 416-418.

portraying several musicians with varying instruments and vocalists

66. In the tomb

of Debeheni, a musical situation during the funeral rites is depicted with singing and

hand-clapping women in the open air in front of a tomb. The building behind the

mu-sicians cannot be the mastaba of Debeheni, because he is buried in a rock tomb and

there is no superstructure above it, as shown in the relief in which the music scene

appears. Therefore, acoustic measurements in front of the tomb are not relevant.

On the tomb façade of Sarenput I, dating to dynasty 12 (1950 BC) at the Qubbet

el-Hawa, the audience consists of only one listener sitting under a canopy,

while three

musicians perform

outside in the open air a short distance away

67.

A special kind of acoustics occurs when the site is surrounded by a wall or palisade.

Enclosures without a roof show different features, as an impulse sound measurement in

a palisade circle reveals

68. “The acoustic properties of a closed space are very different

from those of an open field, i.e. places where the floor is the only boundary. Without

further barriers or obstacles with a large surface no sound reflections can arise”

69.

In

addition to the acoustics inside the system, the minimization of exter nal noise from

out-side through enclosing walls is an important factor.

“

The protection against wind is at

the same time a protection against sound and … also a place for bet ter audibility for any

form of communication”

70.

These acoustic

conditions may corre spond to

the Early

Dy-nastic monumental funerary enclosure of Pharaoh Khasekhemui in Abydos (2709-2682

BC), as well as the so-called “Fort” in Hierakonpolis from the same ruler

71. Through

offerings and seal impressions, it is attested that rituals took place here; however, it is

unknown what kind of ceremonies were performed

72. It can be safely assumed that they

were supported by music or at least recitations, for both of which acoustics are of

parti-cular importance. The area that the monuments cover is very large. The Hierakon polis

Fort measures 67 m × 57 m, the walls are still up to 10 m high and 5 m wide

73.

66These scenes should not to be interpreted as mere representations of entertainment music, but as having a deeper meaning, in detail see Köpp-Junk, Die Anfänge der Musik im Alten Ägypten, 399-404.

67Parkinson, Reading Ancient Egyptian Poetry, fig. 1.4. 68Pomberger et al., „Der Kreisgraben“, 18-28.

69Ibidem, 23, translation by H. Köpp-Junk. 70Ibedem, 27, translation by H. Köpp-Junk.

71 Barbara Adams, Ancient Nekhen. Garstang in the City of Hierakonpolis. Egyptian Studies Asso-ciation Publication 3 (New Malden 1995), 43; Renée Friedman, “Hierakonpolis”. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt 2, ed. Donald. B. Redford, 99-199 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 99; Matthew Douglas Adams, David O’Connor. “The Royal Mortuary Enclosures of Abydos and Hierakonpolis”. In Treasures of the Pyramids, ed. Zahi Hawass, 78-85 (Kairo 2003); Matthew Douglas Adams, David O’Connor. “The Shunet El Zebib at Abydos: Archi tectural con-servation at one of Egypt’s oldest preserved royal monuments”. In Offerings to the Discerning

Eye: An Egyptological Medley in Honor of Jack A. Josephson, ed. Sue D’Auria, 1-7. Culture and

History of the Ancient Near East 38 (Leiden: Brill, 2010), fig. 1-7.

72Laurel Bestock. “The Early Dynastic Funerary Enclosures of Abydos“. ARCHÉO-NIL 18 (2008): 46, 57.

73Renée Friedman. “New Observations on the Fort at Hierakonpolis”. In The Archaeology and

Art of Ancient Egypt, eds. Zahi Hawass, Janet Richards, 309-336. Annales du Service des

Antiquités de l’Égypte Cahier 36 (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2007); Richard L. Jaeschke, Renée Friedman. “Conservation of the Enclosure of Khasekhemwy at Hierakonpolis,

The outer wall of the funerary enclosure of Khasekhemui measures 137 m × 77 m,

and, as in Hierakonpolis, the walls are 5 m thick, but 12 m high, while the in ner wall is

123 m × 56 m, it is only 3 m thick, and has a height of 8 m. Nevert heless, it is unknown

whe

ther rituals consisting of recitations and accompanied by music were performed

inside the monuments or outside. In the funerary enclosure of King Khasekhemui in

Abydos, the foundations of a mudbrick building measuring 18.3 m × 15.5 m were

found, interpreted as offering chapel or cult chapel

74. In the Fort of Hierakonpolis,

a building of 15 m × 10 m was excavated as well

75. Its role is unclear from a musical

point of view; if it was related to music, one might wonder whether music take place

inside or outside of it? In the latter case, the sound would have been reflected not only

by the enclosing walls of the monument itself, but also from the small building.

Spatial Relationship and Volume Measurements

Referring to iconographic evidence, the spatial relationship between audience and

mu sicians in scenes depicting music events can be identified

76. Very often, the group

of listeners is small and they are positioned opposite the musicians at a very short

distance. Old Kingdom scenes show the wife playing the harp for the husband while

sitting on a bed, as in the tomb of Mereruka (ca. 2300 BC)

77and in the one of Pepi

in Meir

78, both mentioned above. A lateral spatial relationship seems to be attested

at the tomb of Sa renput I at the Qubbet el-Hawa

79. Another variation is represented

by the wooden model of Karenen

80, showing him as the only listener in a

“privile-ged position”

81among the musicians

82. They all have in common that there is only

a small distance between listeners and musicians. But of course, temple and tomb

scenes are not photographs, and therefore a specific kind of depiction might depend

on various circumstances such as

the available space, artistic reasons, and the artist’s

Upper Egypt: Investigation, Experimentation and Implementation”. In Terra 2008. Proceedingsof the 10th International Conference on the Study and Conservation of Earthen Architectural Heri tage, Bamako, Mali February 15, 2008, eds. Leslie Rainer, Angelyn Bass Rivera, David

Gan-dreau, 189-193 (Los Angeles: Getty Publication, 2011); “Hierakonpolis, The ceremonial enclosure of Khasekhemwy: The Fort at Hierakonpolis”, accessed September 30, 2020, https://www.hiera-konpolis-online.org/index.php/explore-the-fort.

74The same applies for the funerary enclosures of Hor Aha, Djer, and Peribsen (Bestock, “The Early Dynastic Funerary Enclosures of Abydos”, 42-59, fig. 3, 9-10).

75Renée Friedman. “Investigations in the Fort of Khasekhemwy”. Nekhen News 11 (1999): 9-11. 76Heidi Köpp-Junk. “The artist behind the Ancient Egyptian Love Songs: Performance and

tech-nique”. In Sex and the Golden Goddess II: The World of the Ancient Egyptian Love Songs, eds. Renata Landgráfová, Hana Navrátilová (Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague 2015), 47-49.

77Duell, Mereruka I, pl. 94-95. 78Blackman, Meir V, pl. 45.

79Parkinson, Reading Ancient Egyptian Poetry, fig. 1.4.

80Saqqara, early 12th Dynasty, ca. 1900 BC; Egyptian Museum Cairo, JE 39130; PM III 2, Hick-mann, Ägypten, fig. 36; Parkinson, Reading Ancient Egyptian Poetry, 14.

81Parkinson, Reading Ancient Egyptian Poetry, 35.

ability. Even the artist’s knowledge could be one of the factors, i.e. whether he has

ever seen the scene or the instrument to be depicted. Often, the scenes are based on

different intentions, referring to the con text in which they appear in a tomb or in

a temple. Nevertheless, in the Karenen model, there is no reason to portray it in a way

that differs from an actual musical performance. This increases the probability that

even the small distance shown in the temples and tombs corresponds to the reality in

pharaonic times.

In the following, decibel measurements of replicas of ancient Egyptian instru ments

83and modern equivalents are presented (Tab. 1) because they provide valuable

indica-tions of the purpose of the instruments. If the range is small, it can be assumed that they

were used only in the closest circle or most intimate rituals. High-output musi cal

instru-ments were also playable in an open-air performance, while still being heard.

To get an impression of how loud the instruments and musical activities were,

hand clapping and a natural rattle in the form of a doum palm fruit from Sohag/Egypt

were measured (Tab. 1), because the original form of rattles made of clay or faience

are dried fruits whose seeds produce the rustling sound

84. Moreover, the sound from

a replica of the so-called dancer’s lute

85was measured. It has a slim neck with two gut

strings and six sound holes. According to the iconographic sources, it was not played

with a bow, but with a plectrum

86, so one was used during the measurements. Due to

species protection it has a wooden corpus instead of turtle back as the original lute

has.

Nevertheless, the lute from the tomb of Harmose, dating from ca. 1490 BC, has

a wooden soundboard as well

87. Thus, the measurements of the sounds correspond at

least to some extent to pharaonic times.

The measurements of modern clapsticks made of maple wood should only be seen

as an example. In the tombs of Neferherenptah and Mereruka (2400-2300 BC), the

production of wine is depicted with musicians playing clapsticks

88. In a funeral scene

83For experiences with ancient Egyptian instruments within live concerts see: Köpp-Junk, “Sound of Silence”, 267-283; Heidi Köpp-Junk, “Textual, iconographical and archaeological evidence for the performance of ancient Egypt Music”. In The Musical Performance in Antiquity: Archae ology

and Written Sources, eds. Ventura, Agnès Garcia, Claudia Tavolieri, Lorenzo Verderame, 93-120

(Newcastle upon Tyne, 2018).

84 Hans Hickmann. “Die altägyptische Rassel”. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertums kunde 79 (1954): 122.

85So-called “dancer’s lute”, found in Deir el-Medineh, tomb 1389, 18th Dynasty; Egyptian

Muse-um Cairo, CG 69420; Köpp-Junk, “Textual, iconographical and archaeological evidence”, 95, 106-114, fig. 4-2, 4-4, 4-5; Köpp-Junk, “Sound of Silence”, 270-271, fig. 1. I would like to thank Susanna Schulz (M.A.), musicologist and professional instrument maker from Berlin, very much for this amazing instrument.

86Köpp-Junk, “Textual, iconographical and archaeological evidence”, 107.

87 Scott, Nora. “The Lute of the Singer Har-Mose”. Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Se ries 2, no. 5 (January, 1944): 162.

88Tomb of Neferherenptah, Saqqara, Dynasty 5; Altenmüller, Hartwig. “Arbeiten am Grab des Ne-ferherenptah in Saqqara (1970-1975), Vorbericht”. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäolo gischen

Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 38 (1982): 14–15; Hickmann, Terminologie musicale, Fig. 2; Hick-mann, Ägypten, fig. 47. Tomb of Mereruka, Saqqara, Dynasty 6; HickHick-mann, Ägypten, fig. 47. Perhaps they do not have a round diameter, as the pictorial evidence suggests, but are flat like those in the British Museum (EA 23171, 23172).

in the tomb of Qar in Giza (ca. 2200 BC), an embalmer holds two clapsticks, with one

clapper in each hand

89. The wood of these clapsticks is not specified because none of

them is attested in the archaeological evidence. Moreover, a sistrum, inspired in the

widest sense by one now residing in the British Museum

90, was measured. A modern

round frame drum similar to those existing in ancient Egypt was also included. The

membrane of this modern one is fixed with rivets and not by leather strings as in the

examples from ancient Egypt

91. The round frame drum was not played with sticks

or the knuckles, but with outstretched fingers. Therefore, the same technique was

applied here, while measuring. The replica of the measured lyre is not based on an

Egyptian but on a Greek example now in the British Museum dating from the 4

thto the

5

thcentury BC

92. It should only be seen as an example and not an exact reproduction

of pharaonic times, because it is constructed in a different way. As a counterexample

to these instruments and musical activities, a modern Lakewood D 32cp guitar with

six light steel strings

93was tested. From these instruments and musical activities the

natural rattle and hand clapping are closest to those of ancient Egypt (Tab. 1).

Inspired by Maria Pomberger from Austria, who measured Urnfield culture replicas

of drums

94, these instruments were measured at a distance of 1 m, 3 m, and 5 m. The

measuring took place indoors, the room was 25 m² in size and 2.70 m high, and the

tem-perature was 26 degrees Celsius. The results are shown in the following table (Tab. 1):

Table 1 Decibel measurements (dB) of replicasof Egyptian instruments and modern equivalents

Instrument 1 m 3 m 5 m natural rattle 43 40 40 hand clapping 71 73 72 sistrum low 65 58 55 medium 72 65 63

89Dynasty 6; William Kelly Simpson, The Mastabas of Qar and Idu (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1976), pl. 8.

90British Museum London, EA36310; Anderson, Catalogue of Egyptian Antiquities, 41, figs.70-1. 91 Lise Manniche, “Rare Fragments of a Round Tambourine in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford”.

Acta Orientalia 35 (1973): 29-34, 33.

92British Museum London, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1816-0610-501, EA 1816,0610.501.

93The types of wood used are European spruce, East Indian rosewood, mahogany, and ebony (“Lakewood, Klangkultur made in Germany”, accessed September 29, 2020, https://www.lake-wood-guitars.de/guitar_details.php?series=deluxe&model_id=d-32cp).

94 Beate Maria Pomberger. “Trommeln in der Urgeschichte. Das Beispiel der urnenfelderzeitlichen Keramiktrommel aus Inzersdorf ob der Traisen, Niederösterreich”. Archäologie Österreichs 22/2 (2011): 34-43.

Instrument 1 m 3 m 5 m

loud 75 69 70

clapsticks

68 66 66

round frame drum

low 58 54 46 medium 64 66 63 loud 75 77 73 lute without plectrum 60 55 57 with plectrum 60 58 54 lyre with plectrum 74 65 68

modern western guitar (Lakewood D 32cp)

without plectrum 76 71 63

with plectrum 79 73 71

Of course, the analyzed instruments are not exact replicas, but the hand clapping

and the rattle are definitely authentic. Nevertheless, the measurements give a first

impression, showing for example that the natural rattle has by far the lowest volume.

One should assume that the volume decreases with increasing distance. This is

true for the natural rattle, the low and medium played sistrum, the clapsticks, the

low played round frame drum, the lyre, and the modern guitar,

be it played with

or without a plectrum. However, the volume of the loud played sistrum, of the

lyre and of the lute played without a plectrum rises with increasing distance at

5 m after a decrease at 3 m. This can be explained by the fact that sound needs

a certain distance to unfold. This is obviously favored by the construction of the

in-struments and/or the way they are played, i.e. with or without a plectrum.

The volumes of the rattle and the clapsticks remain the same at 3 m and at 5 m.

Hand clapping and the round frame drum played at medium and loud volume have

their peak at 3 m distance and not at 1 m as one might assume. Moreover, hand

clap-ping is louder than the clapsticks and louder than the round frame drum played at low

and medium volume. Referring to the scene depicting the ensemble of 29 individuals

in the tomb of Iimery

95, the hand clapping was obviously loud enough to give the

rhythm to dancers and musicians, so that drums were not necessary.

The volume of the lute is the same at a distance of 1 m, whether it is played with

or without a plectrum. In comparison to all the other instruments, the natural rattle

produced the lowest volume; this is probably the reason why the artificial ones made

of clay or faience were “invented”.

Sometimes they are provided with holes to make

them even louder

. The difference between the volume at 1 m and at 5 m is 1-3 dB for

the natural rattle, the clapsticks, the medium- and loud-played round frame drum,

and the lute when it is played without a plectrum. A volume loss of 5-6 dB between

95Iimerj Giza, G 6020=LG 16, Dynasty 5, ca. 2450 BC; LD II, Blatt 52.1 m and 5 m

is observed with the loudly played sistrum, as well as with the lute and

lyre played with a plectrum. A difference of 8-10 dB between 1 m and 5 m occurred

with the hand clapping, the low and medium played sistrum, and the guitar when it is

played with a plectrum. The greatest difference in volume between 1 m and 5 m was

12-13 dB, measured on a softly played round frame drum and a guitar played with

a plectrum. The volume loss between the measurements at 1 m and 3 m was 2-9 dB.

It should be noted that 10 dB approximately halves or doubles the volume. The sound

pressure level develops exponentially, but the perceived loudness is linear.

As mentioned above, very often the group of listeners is small and they are

posi-tioned opposite the musicians at a very short distance

96. This small distance is

there-fore not necessarily due to a lack of space on the tomb walls, but maybe caused by the

acoustic conditions of the instruments. A distance of 1-3 m seems to be perfect, be it

a lateral or frontal relationship of listeners and musicians. Referring to the

experi-ments of Pomberger with European drums, the volumes decreased at a measuring

distance of 5 m, and the greatest volume development occurred at a distance of 3 m

97.

Résumé

In some locations, it can only be assumed that music was performed, while in others

it is even depic ted. What is certain is that music took place in residential buildings,

although we do not know exactly what they looked like or where the music

perfor-mance was located within a building. Furthermore, there are sources showing that

music was played open air and under canopies. It is likely to suggest that music took

place in temples and tombs, but no representation shows precisely where the

per-formance took place in these lo calities. The scene in the tomb of Debe heni shows

a musical performance accompanying certain rituals in front of the tomb, not in the

accessible interiors or even close to the burial itself. Therefore, there are still several

questions as to which Egyptian architecture was predestined for singing, which one

for idiophones or other instruments? Are the acoustic conditions within the funerary

chapel of a mastaba better than outside? Referring to the tombs, the question arises

of whether the position in front of the false door with its special architectural features

consisting of recesses and protrusions is the best acoustic location to recite the

sacrifi-cial formula, or whether the volume was not important and the place where the rituals

took place was chosen due to other reasons.

Other questions include the following: Where are the music scenes depicted,

and where did they actually take place? Is it reasonable to assume that the place in

a temple or tomb where musical activity is shown or mentioned is the same as the

one in which the musical performance took place? Is there a connection between

the musical scenes depicted in tombs and temples, and the acoustic

character-istics of the localities as in several European caves, where the positions of

96Köpp-Junk, The artist behind the Ancient Egyptian Love Songs, 47-49.the

paintings

98are associated with the best acoustic situations? To answer these

ques-tions the Greco-Roman period temple of Athribis (first century BC – first century

AD), dedicated to the goddess Repit, is used as an example. At the western outer

wall M3, two females are depicted playing round frame drums. The musicians stand

be hind the Roman emperor Claudius, of whom only the crown is preserved, who

offers a bull along with further sacrifices to Sokar, Horus, and Repit

99. At first sight,

one could assume that the performance shown on the wall took place in the area,

in which it is depicted. Hence, an analysis of the acoustic features at the location

in front of the wall would be extremely useful. The enclosing wall of the temple

is located about 40 m west of wall M3; therefore, there would be enough space, as

one might suppose. Nevertheless, it is unclear what existed originally to the west of

the wall because a monastery build ing was erected there in later times. But it

can-not be assumed that it was an empty area at the time when the temple was used.

However, from a text on door M3-J2 it is known

that there was a kitchen to the

west of it, used to prepare the offerings

100. Thus, the author as well as the excavator

Dr Marcus Müller assume that music did not take place in the yard in front of wall

M3, but only in the temple itself

101. Based on this example, it is obvious that the

loca-tion of a music scene does not have to match the place of performance. The quesloca-tion

of whether music took place where it it is portrayed or attested by texts cannot be

ans-wered mono-causally; this must be examined individu ally for every piece of evidence.

Referring to the large ensemble of 29 individuals depicted in the tomb of Iimery,

it is apparent that hand clapping was loud enough to provide a rhythm, so that the

musicians and dancers could follow the beat; therefore, drums or clappers were not

necessary.

The measuring of the volume and sonic properties of the replicas of the

ancient Egyptian instruments makes relevant information about their use available:

whether they were only used at short distances, i.e. with a small audience nearby, or

whether they were used in larger venues providing space for more listeners.

The

ana-lysis provides new insights into the fields of Egyptology, music archaeology,

archaeo--acoustics, and sound archaeology. Nevertheless, this study is just the basis, upon

which further research can build.

98Till, Sound Archaeology, 666.

99Scene M3 51, for the publication of the texts of the temple wall see Christian Leitz, Daniela Mendel-Leitz, Athribis VI. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 2020, 152-153, for the translation see Christian Leitz, Daniela Mendel-Leitz, Athribis VII, 689-691, I would like to thank both of them most sincerely for providing me with their previously unpublished material. For a plan of the temple see Marcus Müller. Athribis V: Archäologie im RepitTempel zu Athribis

20122016 II, Tafeln. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 2019, pl. 1. In detail on

the scene with the round frame drums and other musical items in the temple of Athribis see Heidi Köpp-Junk, “Musik im Tempel von Athribis: Sistrum, Menit, runde Rahmentrommel und Glöck-chen aus einer Kultstätte griechisch-römischer Zeit”. Submitted for publication in Athribis VIII, eds. Marcus Müller, Christian Leitz (Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale).

100For the text see Leitz, Mendel-Leitz, Athribis VI, 10, for the translation Leitz, Mendel-Leitz,

Athribis VII, 396-397.

Abbreviations

PM III - Porter, Bertha, Rosalind L.B. Moss. Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, reliefs and paintings. III, Memphis (Abû Rawâsh to Dahshûr). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1931.

LD - Lepsius, Carl Richard. Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien 110. Berlin: Weidmann, 1849-1858.

Bibliography:

Adams, Barbara. Ancient Nekhen. Garstang in the City of Hierakonpolis. Egyptian Studies As-sociation Publication 3. New Malden 1995.

Adams, Matthew Douglas, David O’Connor. “The Royal Mortuary Enclosures of Abydos and Hierakonpolis”. In Treasures of the Pyramids, ed. Zahi Hawass, 78-85. Kairo 2003. Adams, Matthew Douglas, David O’Connor. “The Shunet El Zebib at Abydos: Architectural

conservation at one of Egypt’s oldest preserved royal monuments”. In Offerings to the Dis cerning Eye: An Egyptological Medley in Honor of Jack A. Josephson, ed. Sue D’Auria, 1-7. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 38. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Altenmüller, Hartwig. “Arbeiten am Grab des Neferherenptah in Saqqara (1970-1975), Vorbe-richt”. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 38 (1982): 1-16.

Anderson, Robert. Catalogue of Antiquities in the British Museum III: Musical Instruments. London: British Museum Press, 1976.

Arnold, Dorothea. When the Pyramids were built. New York: Rizzoli, 1999.

Backhaus, Hermann, J. Friese, E.M. v. Hornbostel, Alfred Kalähne, H. Lichte, E. Lübcke, Erwin Meyer, Eugen Michel, Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, H. Sell, Ferdinand Tren-delenburg. Handbuch der Physik VIII, Akustik. Berlin: Springer, 1927/2012.

Bestock, Laurel. “The Early Dynastic Funerary Enclosures of Abydos“. ARCHÉONIL 18 (2008): 42-59.

Bietak, Manfred. “Eine „Rhythmusgruppe” aus dem späten Mittleren Reich”. Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes 56 (1985): 3-18.

Blackman, Aylward Manley. “The Rock Tombs of Meir Part V”. Archaeological Survey of Egypt 28, London: Egypt Exploration Society, 1953.

Cauville, Sylvie, Didier Devauchelle. Le Temple d’Edfou I. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1984.

Chassinat, Émile. Le mystère d’Osiris au mois de Khoiak. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéolo-gie Orientale, 1966-1968.

Debertolis, Paolo, Niccolò Bisconti. “Archaeoacustics Analysis and Ceremonial Customs in an Ancient Hypogeum”. Sociology Study 2 (10) (2013): 803-814.

Diaz-Andreu, Margarita, Carlos Garcia Benito. “Acoustic Rock Art Landscapes: A Compari-son between the Acoustics of three Levantine Rock Art Areas I Mediterranean Spain”. Rock Art Research 32 (1) (2015): 46-62.

Duell, Prentice. The Mastaba of Mereruka I: Chambers A 110. Oriental Institute Publications 31, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1938.

Edel, Elmar. Das Akazienhaus und seine Rolle in den Begräbnisriten. Münchner Ägyptologi-sche Studien 24, Berlin: B. Hessling, 1970.

Kurt Eggenschwiler, Karl Baschnagel. Aktuelle Aspekte der Kirchenakustik. Dübendorf: Eigenverlag, o.J., 1-8.

Emerit, Sibylle, Dorothée Elwart. “Sound Studies and Visual Studies applied to Ancient Egypt”. In Sounding Sensory Profiles in the Ancient Near East, eds. Annette Schellenberg, Thomas Krüger, 315-334. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2019.

Emery, Walter Bryan. “Great Tombs of the First Dynasty III”. Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Society 47, London: Egypt Exploration Society, 1958.

Fischer, Henry George. Egyptian Women of the Old Kingdom and the Heracleopolitan Period. New York 2000.

Friedman, Renée. “Investigations in the Fort of Khasekhemwy”. Nekhen News 11 (1999): 9-12. Friedman, Renée. “Hierakonpolis”. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt 2, ed.

Don-ald. B. Redford, 99-199. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Friedman, Renée. “New Observations on the Fort at Hierakonpolis”. In The Archaeology and

Art of Ancient Egypt. Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor, eds. Zahi Hawass, Janet

Richards, 309-336. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2007.

Hickmann, Hans. La trompette dans l’Égypte ancienne. Supplément aux Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 1, Kairo 1946.

Hickmann, Hans. Instruments de musique: Nos. 6920169852. Catalogue général des anti-quités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire. Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale: Cairo 1949.

Hickmann, Hans. “Le tambourin rectangulaire du Nouvel Empire. Miscellanea Musicologica X”. Annales du Service des antiquités de l’Égypte (1951): 317-333.

Hickmann, Hans. “Die altägyptische Rassel”. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Alter tumskunde 79 (1954): 116-125.

Hickmann, Hans. “Terminologie musicale de l’egypte ancienne”. Bulletin de l’Institut d’Égypte

36 (1955): 583-618.

Hickmann, Hans. “Die Gefäßtrommeln der Ägypter”. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologi

schen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 14 (1956): 76-69.

Hickmann, Hans. Ägypten. Musik des Altertums II. Leipzig: Deutscher Verlag für Musik, 1961.

Jaeschke, Richard L., Friedman, Renée. “Conservation of the Enclosure of Khasekhemwy at Hiera konpolis, Upper Egypt: Investigation, Experimentation and Implementation”. In Ter

ra 2008. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Study and Conserva tion

of Earthen Architectural Heritage, Bamako, Mali February 15, 2008, eds. Leslie Rainer,

Angelyn Bass Rivera, David Gandreau, 189-193. Los Angeles: Getty Publica tion, 2011. Kleinitz, Cornelia, Rupert Till, Brenda Baker. “The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project –

Ar-chaeology and acoustics of rock gongs in the ASU BONE concession above the Fourth Nile Cataract, Sudan: a preliminary report”. Sudan & Nubia 19 (2015): 106-114.

Kleinitz, Cornelia. “Soundscapes of the Nile valley: ‘Rock music’ in the Fourth Cataract re-gion”. In Challenges and Aims in Music Archaeology, eds. Arnd Adje Both, Ricardo Eich mann, Ellen Hickmann, Lars-Christian Koch, 131-146. Studies in Music Archaeology VI. Rahden, Westfalen: Leidorf, 2008.

Kleinitz, Cornelia. “Acoustic Elements of (pre)historic Rock Art Landscapes at the Fourth Cataract”. PAM Supplement Series 2.2/1, Warsaw 2010: 149-160.

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. Die Anfänge der Musik im Alten Ägypten vom 5. Jt. v. Chr. bis zur 4. Dynas

tie (manuscript finished).

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “Göttliche Klänge. Zur manipulativen Kraft der Musik im Alten Ägypten”. In Die geistige Macht der Musik, ed. Jean Ehret. Luxemburg (submitted for publication).

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “Rasseln für die Ewigkeit: Die ältesten Perkussionsinstrumente des Alten Ägypten“. Submitted for publication in: Ancient Percussion Instruments: Organology – Perceptions – Multifunctionality, ed. Arnaud Saura-Ziegelmeyer, Revue PALLAS. Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “Musik im Tempel von Athribis: Sistrum, Menit, runde Rahmentrommel

und Glöckchen aus einer Kultstätte griechisch-römischer Zeit”. Submitted for publication in Athribis VIII, eds. Marcus Müller, Christian Leitz. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “The Earliest Music in Ancient Egypt”. ASOR (American School of Ori

ental Research) VI, Nr. 1 (January 2018),

http://www.asor.org/anetoday/2018/01/earliest--music-egypt.

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “Textual, iconographical and archaeological evidence for the performan-ce of ancient Egypt Music”. In The Musical Performanperforman-ce in Antiquity: Archaeology and

Written Sources, eds. Ventura, Agnès Garcia, Claudia Tavolieri, Lorenzo Verderame,

93-120. Newcastle upon Tyne 2018.

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “Sound of Silence? Neueste Ergebnisse aus der Musikarchäologie”. In

Pérégrinations avec Erhart Graefe. Festschrift zu seinem 75. Geburtstag, eds. Anke

Blö-baum, Marianne Eaton-Krauss, Annik Wüthrich, 267-283. Ägypten und Altes Testament 87, Münster: Zaphon, 2018.

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “Musik im Alten Ägypten”. Sokar 33 (2016): 26-33.

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “Ägyptische Religion – Götter, Tempel und deren Ursprung”. In Von den

Ufern des Nil nach Luxemburg, ed. Michael Polfer, 35-41. Luxemburg: MNHA, 2015.

Köpp-Junk, Heidi. “The artist behind the Ancient Egyptian Love Songs: Performance and technique”. In Sex and the Golden Goddess II: The World of the Ancient Egyptian Love

Songs, eds. Renata Landgráfová, Hana Navrátilová, 35-60 (eds.). Prague: Czech Institute

of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague 2015.

Köpp, Heidi. “Ägypten und die 10 Gebote heute: Hollywoods Bild von Ägypten im Spiegel der modernen Forschung”. In Verschlungene Pfade. Neuzeitliche Wege zur Antike, ed. Rainer Wiegels, 203-216. Rahden, Westfalen: Leidorf, 2011.

Kurth, Dieter: Treffpunkt der Götter. Inschriften aus dem Tempel des Horus von Edfu. Zürich, München: Artemis-Verlag, 1994.

Lawergren, Bo. “Music”.In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt 2, ed. Donald. B. Red-ford, 450-454. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Leitz, Christian, Daniela Mendel-Leitz, mit einem Beitrag von Susan Böttcher. Athribis VI. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 2020 (in press).

Leitz, Christian, Daniela Mendel-Leitz. Athribis VII. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 2020 (in press)

Lichtheim, Miriam. Ancient Egyptian Literature II: The New Kingdom. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Manassa, Colleen. “Sounds of the Netherworld”. In Mythos und Ritual. Festschrift für Jan

Assmann zum 70. Geburtstag, eds. Benedikt Rothöhler, Alexander Manisali, 109-135.

Münster: LIT Verlag, 2008.

Manassa, Colleen. “Soundscapes in Ancient Egyptian Literature and Religion”. In Laut und

Leise: Der Gebrauch von Stimme und Klang in historischen Kulturen, ed. Erika

Meyer--Dietrich, 147-172. Bielefeld: transcript-Verlag, 2011.

Manniche, Lise. “Rare Fragments of a Round Tambourine in the Ashmolean Museum, Ox-ford”. Acta Orientalia 35 (1973): 29-34.

Manniche, Lise. “Ancient Egyptian Musical Instruments”. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien 34, München: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1975.