Aneta Syta

Department of Speech Therapy and Voice Emission, University of Warsaw

0000-0001-7487-4083

Kinga Ziobrowska

Student of General and Clinical Speech Therapy, Warsaw Medical University

Influence of Ankyloglossia on Primary Functions

Abstract: The aim of this article is to capture the influence of shortened tongue frenulum (ankylo-glosia) on primary functions such as breathing, sucking, swallowing, as well as on food activities – biting and chewing. The publication is a review and is an attempt to combine the available profes-sional literature (national and world) on the above topic, as well as to discuss the conclusions from the cited studies. One of the paragraphs is devoted to several cases of children with ankyloglossia and its impact on primary activities in these children. The article also includes own reflections and considerations from the literature and case description discussed in the publication, children with shortened sublingual frenulum.Key words: ankyloglossia, primary functions, tongue frenulum, vertical and horizontal position of the tongue

The impact of ankyloglossia on the primary functions

Shortened frenulum of the tongue is not something that can be easily defined and described. The image of ankyloglossia is not uniform: in different people, the frenulum may have different levels of shortening, attachment place, loca-tion manner in relaloca-tion to the tongue surface itself (in other words, the external frenulum or hidden under the tongue mucosa), fold shape, elasticity, resilience, etc. Therefore, it can affect the quality of pronunciation in a different way, and earlier the primary activities. Ankyloglossia is an anatomical defect that appears immediately after birth and has a significant impact on the child’s functioning during later development. Despite this, older children come to the speech therapy room, already with complex problems associated with the shortened frenulum. To prevent this, it is important for both speech therapists and medical staff, e.g. midwives, to be able to recognize a short frenulum in newborns and assess this risk of adverse effects at a later time.

Ankyloglossia

The first use of the “ankyloglossia” term appeared in the English-language medical publication in the 1960s, when Anthony F. Wallace defined the tongue-tie as “[…] the condition in which the tip of the tongue cannot protrude beyond the lower incisors due to a short frenulum, often containing a scar” (Suter & Born-stein, 2009; Wallace, 1963). It has also been described in Poland that “[…] anky-loglossia (ankylosis ligule, anky“[…] anky-loglossia, anky“[…] anky-loglossia interior) is a developmen-tal disorder involving the underdevelopment of the frenulum of the tongue and attachment to the bottom of the mouth, which prevents (hinders) its movement” (Ostapiuk, 1997, p. 132).

In the medical literature, one can find information that the frenulum of the tongue is a tissue fold that connects the bottom of the mouth with the lower sur-face of the tongue. It is an embryological residue that arises as a result of unfin-ished apoptosis occurring in the previous process of separation of the tongue mass from the bottom of the mouth. If the abovementioned phenomenon is dis-torted, the tongue will be attached to the bottom of the mouth to a moderate or significant degree. Such an anomaly in structure is referred to as ankyloglossia. The short frenulum is usually an isolated defect, yet it happens to coexist with some syndromes, e.g. Kindler, Beckwith Weidmann, cleft palate coupled with the X chromosome (Stańczyk, Ciok, Perkowski, & Zadurska, 2017, p. 124).

Incidence of ankyloglossia

The incidence of ankyloglossia is difficult to determine because it depends on the adopted criterion for assessing the condition of the frenulum. However, in the canon of medical and speech therapy publications, one can read that the defect is more common in boys than in girls. This difference in incidence is explained by better knowledge of the classification and the ability to recognize ankyloglos-sia among the staff and the treatment of a short posterior frenulum – which for many years has been undiagnosed and recognized as the norm – as a defect in the tongue structure (Sioda, 2012, p. 118). In addition, many researchers set the incidence of ankyloglossia at 0.02 to 10.7% and indicate that this defect is found in boys from 1.5 to 3 times more often than in girls (Ballard, Auer, & Khoury, 2002, p. 16; Stańczyk et al., 2017, p. 124; Suter & Bornstein, 2009).

Treatment and rehabilitation

There are several suggestions for treating a short tongue frenulum in the lit-erature on the subject. Speech therapists present various positions that they seem appropriate, but so far no uniform treatment and rehabilitation scheme for anky-loglossia has been developed. It seems that the controversy regarding the treat-ment of ankyloglossia in the view of various authors and researcher are mainly related to different views referring to the so-called possibilities or inability to stretch this structure.

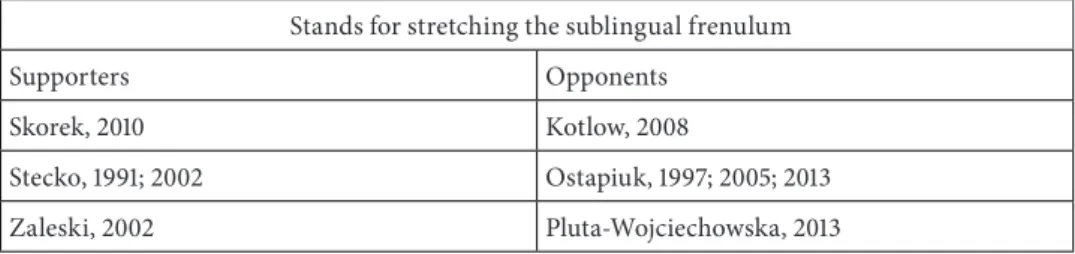

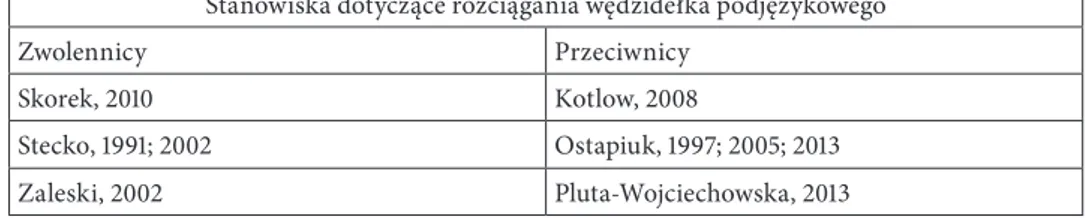

Table 1. Stands of researchers regarding the stretching of the sublingual frenulum Stands for stretching the sublingual frenulum

Supporters Opponents

Skorek, 2010 Kotlow, 2008

Stecko, 1991; 2002 Ostapiuk, 1997; 2005; 2013

Zaleski, 2002 Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013

Source: Own study based on: Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sambor, 2016, p. 134.

The table above presents only examples of authors who, as supporters of stretching the frenulum through massage, describe the importance of this method for improving the function and articulation habits. It can be deducted from the table that it was supported in much older publications. On the other hand, the newer ones show the negative impact of the massage, while noting the benefits of surgical procedures.

It is worth noting that Polish and foreign publications do not describe research that would confirm the effectiveness of tissue fold massage in its stretching. What is more, there are reports confirming its negative effects. Roberta Martinelli and her colleagues (2014) conducted research on the structure of the tongue frenulum. They found that it was made of the mucosa fold, which consists of type I colla-gen fibres and elastin fibres. They proved that these structures are not subject to stretching, they are even resistant to this movement and provide the opportunity to return to its original length. Due to the location of such fibres in the frenulum, extensibility is not possible in any of the frenulum types (anterior, posterior, etc.).

Danuta Pluta-Wojciechowska and Barbara Sambor (2016, pp. 127–131) noticed that the massage may have a negative effect manifesting in breaking the frenu-lum continuity. Such information was obtained from interviews collected from some mothers of children with ankyloglossia who, at the instigation of speech therapists, massages this structure and led to the appearance of blood and swell-ing. Reluctance to perform surgical procedures may be associated with the belief

of some therapists and some specialists (orthodontists, paediatricians, etc.) that undercutting the frenulum is a way of harming the child.

“Surgical treatment” of the frenulum in newborn was already used at least 3,000 years ago, by tearing its structure with a fingernail. As you can see, this “procedure” deviates to a large extent from modern methods of treatment, but it shows that the consequences of ankyloglossia in later physiological activities have been known for years. In Poland, this problem was appreciated in 2012, where at the 5th Congress of the Lactation Science Centre, a frenulum examination and its undercutting were introduced to the standard care for every newborn baby (Ostapiuk, 2015, pp. 659–660).

Due to the construction of the short frenulum, different types of treatment are distinguished: frenotomy, frenectomy, frenoplastics. In the youngest children, the first two types of treatment are considered to be the initial ones, which means the successive: undercutting of the frenulum and total excision of the frenulum. The frenoplastics procedure, i.e. various methods of its correction, is considered to be a later stage. In newborns, a frenotomy is done without anaesthesia, but it is necessary for older children. In some cases, one-time surgery is not enough and often additional corrections are inevitable. The cutting of the frenulum along will not solve the problem with which the child was reported for surgery. Such reasons mainly include problems with feeding the baby, and in fact with the inability of the child to suck the mother’s milk and in the case of an older child – problems with pronunciation. Therefore, it is very important to do exercises before and after the procedure.

For a small child, of course, sucking is a natural exercise for the frenulum. After the procedure, the child is immediately put to the breast. An older child who has already developed speech to a greater or lesser degree requires exercises verticalizing the tongue that are carried out by a speech therapist – both before and after the procedure. As with any other procedure, we can also find contrain-dications here. If a newborn baby has problems with blood clotting or a congeni-tal disease of the motor unit, he or she may not be qualified for surgery because of the high risk of the tongue shifting towards the throat and causing breathing and swallowing problems (Sioda, 2012, pp. 121–122).

Primary functions

Primary functions are based on primary motor skills and include activities such as breathing, foot intake and drinking. However, it should be mentioned that this term is not limited to the functions listed above. Facial expressions, self-stimulation, self-play within the oral-facial complex, and physiological activities

such as coughing and yawning – these are elements that indicate the broader meaning of this concept (Malicka, 2013, p. 47).

These functions are shaped during the prenatal period. This stage is not only the modelling of a specific base of multi-track activities, but also the proper training of organs, which over time will initially participate in primary activi-ties, and later in the production of the phonic substance. The publication of Pluta-Wojciechowska (2013, pp. 55–56) describes research that shows that up to the 16 week of the foetal life, during the day the child displays about 20,000 various movements that also occur around the face and the masticatory organ. However, in the second half of the first trimester, multiple symptoms can be observed, which appear at different times and include, for example, turning the neck and the torso to the stimulus of the upper lip, uptake, pushing out and, with time, swallow-ing foetal waters, suckswallow-ing of the thumb may occur, which in some cases can be observed during a standard ultrasound examination, and the work of muscles involved in breathing outside the mother’s womb.

Breathing

Breathing is a function necessary to live and it is an u reflex. When charac-terizing breathing, the following elements should be taken into consideration: the inhalation and exhalation path, the position of articulatory organs and the type of breath (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, pp. 78–79). The breathing mechanism distin-guishes the inhalation and exhalation phase. Irena Malicka (2013, p. 48) describes three ways of breathing: so-called pectoral, abdominal-diaphragmatic (abdominal) and abdominal-thoracis, i.e. the most effective respiratory path, involving both the muscles of the chest, diaphragm and abdomen.

After delivery, a healthy newborn should breathe through the nasal passage. As Urszula Kossakowska writes “[…] nasal breathing is the only way of physi-ological breathing in the first months of human life” (Skorek & Rządzka, 2011, p. 15). The oral route is activated in a person during dynamic breathing, where there is increased physical effort or basic speaking activity. In this situation, the air is taken in both the oral and nasal paths (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, p. 79).

Suction

Sucking is the first way for a baby to consume food. This is a complex activ-ity that requires coordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing. Approxi-mately 56 muscles, 5 cranial nerves, as well as spinal and chest nerves (Sioda, 2012, p. 117) are responsible for this synchronization. Many authors agree that the sucking reflex gradually disappears, which is particularly responsible for the child’s mental and somatic development, as well as progressive nervous devel-opment (Łuszczuk, 2013, p. 59). The moment of complete disappearance of this reflect occurs about the 12 month of human life. It is important that until then, the child learns to take food from a spoon, drink from a cup and bite off foods of a harder consistency (Malicka, 2013, p. 47).

Swallowing

The swallowing process accompanies man from birth, and even – as described at the beginning of this chapter – already in the foetal life. In order for swal-lowing to develop properly, the proper functioning of both the peripheral and central nervous system is particularly important, as well as the harmonization of the muscle work and breathing. According to William R. Proffit and Henry W. Fields, a person performs swallowing several time an hour at night, while on average 800 times during a day, which in total gives about a thousand swallows a day. There are three swallowing phases in a man: oral, pharynx and oesopha-geal. The first phase depends on the will, while the other two are not controlled (Proffit, Fields, & Sarver, 2007, p. 344).

It is important that the swallowing process in children and adults is not the same. The transformation of the swallowing methods from visceral (infantile, child’s) to somatic (mature) refers to the development of the stomatognathic sys-tem, associated with the levelling of the physiological posterior occlusion, the appearance of more deciduous teeth and the extension of the face in the lower section. There are dissonances in the literature regarding the time when a child should already breathe in a mature way. However, the period of three years of age is considered the beginning of somatic swallowing (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2011, pp. 140–141).

Biting off

The appearance of milk incisors, between the 8and 10 month of age, is the beginning of the biting activity. One should know that there are several ways of biting off. Both adults and children have one and the same mechanism, which does not change with the maturation. The rhythm of the activities performed in this process appears in a specific order. At first, the mandible lowers and the top and bottom incisal edges are set in the opposite manner, then the contraction of muscles causes the structures described above to slide relative to each other and a bite of the solid food occurs. The speech therapist should be able to assess how a child bites off the food and know that any place other than the plane of the upper and lower incisors performing this activity already constitutes a disorder (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, p. 90).

Biting and chewing

The next primary functions that are revealed after mastering the biting off include biting and chewing. The biting activity starts shaping along with the stage of the appearance of the next milk teeth, while chewing occurs after the biting training, usually with the appearance of molars (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, pp. 92–93).

In the early stages of a child’s life, the speech therapist can assess the abil-ity of the functions described above. The first is the bite reflex that can be seen in a child from birth to even 4, and in extreme cases 7 months of age. To assess this reflex, put your fingertips on the upper gums around the fangs. The correct reaction to such a stimulus is rhythmic lowering and raising of the jaw. In con-trast, the chewing reflex, which is associated with the biting reflex, begins in the 4 month of life.

Touching the lips, teeth or mouth causes the jaw to move in a vertical plane, i.e. abduction and adduction motions. However, Pluta-Wojciechowska reports that biting and chewing differ the movement performed in a different number of planes. In the case of biting, these are two planes resulting from raising and lowering of the mandible, while chewing requires movements in three planes, in which the first two correspond to the movements during biting, and the third is the so-called sideways movement of the mandible (Skrzek, 2016, p. 348).

The secondary difference between biting and chewing lies in the consistency of processed foods. When it comes to chewing functions, they are much harder and have a specific architecture. Thus, it can be concluded that the chewing

func-tion is activated when biting is insufficient, and the food should be addifunc-tionally crushed, which requires the use of greater strength and activity of the articula-tory organs (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, pp. 93–94).

The impact of ankyloglossia on primary activities

To understand the essence of this paragraph, one should first know the mecha-nism of operation of specific primary functions, know that tongue is one of the most important organs involved in most activities of the stomatognathic system and that the consequence of its structural anomalies, mainly the shortened frenu-lum, will be the lack of verticalization of this muscle (otherwise disturbed verti-cal-horizontal position) and the limitation of its mobility (Kaczmarek & Łysiak-Seichter, 2005, p. 134; Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sambor, 2016, p. 142; Stańczyk et al., 2017, p. 123).

In addition to the possible analyses of the significance of the shortened tissue fold in newborn and infants described earlier, an additional help may be provided by the study presented by Pluta-Wojciechowska, which is an anatomical and func-tional assessment. The most important conclusion that the author made when analysing the functions of breathing, eating, drinking and swallowing is that the vertical-horizontal position is the most important position of the muscle involved in breathing and somatic swallowing (Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sambor, 2016, pp. 135–136, 141). It was also emphasized that the short tongue frenulum modifies the position of the tongue, especially in early life and impairs oral development (Huang, Quo, Berkowski, & Guilleminault, 2015).

To understand the way in which the short frenulum affects the mobility and work of the tongue, one should know that:

■ fragments of individual muscles are connected together in different parts, and the activity of individual muscles of the tongue affects the activity of the entire organ;

■ tongue is an articulatory organ of the same volume but variable shape;

■ .limiting the movement of the organ even in one direction causes the move-ment of the entire tongue in a divergent way (the involvemove-ment of the internal and external muscles of the tongue);

■ coordinated and non-disruptive work of all muscles of the tongue depends on the performance of a specific tongue function (Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sam-bor, 2016, p. 152).

Ankyloglossia and breathing

“There have been reports of frequent co-occurrence of ankyloglossia with epi-glottis and larynx dislocation manifested in newborn babies with dyspnoea and skin defects, and in adults – with respiratory failure and snoring” (Stańczyk et al., 2017, p. 131). The literature on the subject distinguishes between two factors of pathological oral breathing. These are systemic and local factors. The local fac-tors include disorders that cause complete or partial nasal congestion, as well as: adnate frenulum, short upper lip, malocclusion, macroglossia and muscle hypo-tonia (Łuszczuk, 2013, p. 56). The base of the tongue in the throat has the ability to shape its muscles. However, the part of the tongue that is located in the middle of the mouth is crucial for the development of the jaw, the shape of the face and nasal passages in the upper respiratory tract. Incorrect tongue structure causes facial muscles dysfunction, which in turn leads to respiratory problems, includ-ing the obstructive sleep apnoea (Linclud-ingual, labial, frenums…).

Ankyloglossia and suction

Suction is one of the primary functions that requires the simultaneous activ-ity of many articulatory organs. These structures include primarily lips, tongue and mandible (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, p. 95). The tongue mechanism is extremely important in the process of breast sucking. In the act of sucking, the tongue makes several different movements: it holds the nipple, together with the cheeks, it creates a negative pressure in the mouth and covers the alveolar edge of the jaw and performs protrusion, retrusion and peristaltic movements. In a situation where the mobility of the tongue is limited by the presence of anky-loglossia, the natural adaptability of the newborn may not be enough, and as a result tongue disorder will appear, which will cause incorrect breast sucking or complete inability to do this (Sioda, 2012, p. 126).

Estimates show that nearly 13% of feeding problems may be dependent on the incorrect construction of the tongue frenulum. “Babies with a short frenulum cannot stick their tongue farther than the lower alveolar ridge and either press the nipple with the ridge, or press the base of the nipple with the ridge and can-not hold it” (Stańczyk et al., 2017, p. 126).

In the publication of Magdalena Nehring-Gugulska, Monika Żukowska-Rubik and Agnieszka Pietkiewicz (2017, p. 7) one can read that when the front frenulum is shortened, it is observed that the breast cannot be stabilized and the negative pressure necessary for effective milk intake by the infant is observed. As a result,

it may be accompanied by biting the breast and smacking. As the authors note, not every type of ankyloglossia prevents breast sicking. A similar position is taken by Pluta-Wojciechowska and Sambor (2016, p. 134), whose research showed that many babies with ankyloglossia could perform the sucking, but in the future they had speech impediments. It is worth noting that it is not only important that the children performed the sucking, but also the way they did it.

In English-language literature, there were studies that aimed to check whether the presence of ankyloglossia affects the process of breastfeeding. One such analy-sis is a study by researchers at the Department of Paediatrics of the Cincinnati Medical University in Ohio, which included 2,763 breast-fed infants, including 273 outpatient infants with breast-feeding problems for possible ankyloglossia, and each child with ankyloglossia was evaluated using a risk assessment tool for the tongue function of the frenulum. Researchers watched each child while breastfeeding. In a situation where there were problems with clenching the baby’s teeth on the breast, mothers had to describe the sensation and quality of the baby sucking the breast, and if the pain occurred, to characterize it on a scale of 1 to 10. If a child was diagnosed with ankyloglossia, mothers agreed to carry out a frenotomy surgery for their children. The results showed that the shortened frenulum occurred in 88 (3.2%) hospitalized patients and in 33 (12.8%) outpatient children. After frenotomy, the latch improved in all cases, and the level of pain in the mothers dropped significantly (Ballard et al., 2002).

Ankyloglossia and swallowing

Tongue is the basic organ involved in swallowing. Two types of swallowing have already been described, which include visceral, or infantile, and somatic, so-called mature swallowing. The second one requires the tongue to be set in a vertical-horizontal position. This position requires the wide tongue to be upright, where one part is raised and the apex adheres to the incisive papilla behind the incisal teeth, while mediodorsum is glued to the palate, and the sides of the tongue adhere to the upper molars and premolars, and on the other side, the tongue takes on a wide shape (Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sambor, 2016, p. 136).

It is important to know that when the tongue is in the position described above, it creates forces similar to those of a contracting muscle. In addition, together with the short frenulum, the hyoglossus muscle modifies the correct position of the hyoglossus with the resulting elevation and forward shift in the hyoid bone. In a dynamic situation, ankyloglossia limits the ability to perform certain movements necessary in the process of swallowing, which causes various consequences, in particular:

■ the short tongue frenulum acts as an anterior, anatomical limitation for the bicep and digastric muscle, which during contraction cannot move the hyoid bone properly;

■ the tongue cannot hit the hard palate but remains attached to the bottom of the mouth;

■ infrahyoid muscles cannot stabilize the hyoid bone, and this causes abnor-mal flexion of the cervical spine and head (Dezio, Piras, Gallottini, & Denotti, 2015, p. 5).

Thus, the proper swallowing process is not only the verticalization of the front part of the wide tongue, but also other parts and the role of many muscles, mainly the external tongue, which coordinate the work of the whole muscle, so that the bolus us displaced to the digestive tract. Pluta-Wojciechowska (2013) distinguishes factors that favourably affect the transformation of swallowing from visceral to somatic, and one of them is “the correct structure of the tongue, including the size and condition of the tongue frenulum” (p. 105).

Ankyloglossia and gastrointestinal activities

Biting off

The process of biting off has already been described, yet it should be recalled that the tongue plays a significant role in this process. Important aspects of bit-ing off are primarily the work of the muscles raisbit-ing and lowerbit-ing the lower jaw, the work of the tongue involving the movement of food respiratory coordina-tion (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, p. 90). The development of biting off skills is stimulated by giving the child increasingly harder foods. “When performing the described operation, food bitten off with incisal teeth must be placed in the mid-dle of the tongue, as a result of which it is possible to make the verticalization movement of the apex” (Skrzek, 2016, p. 353).

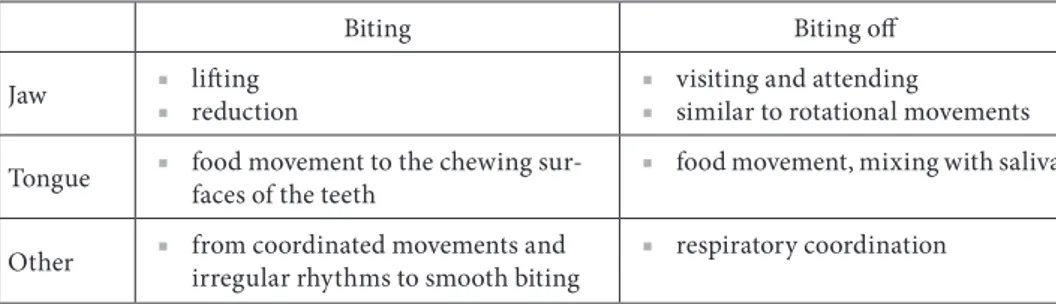

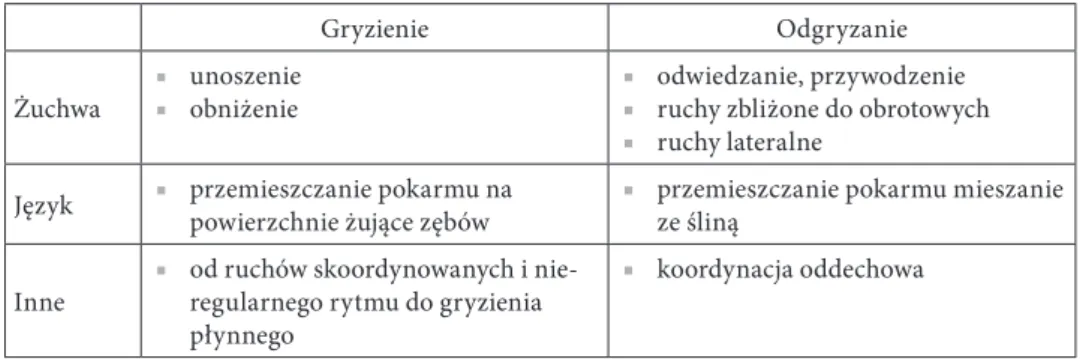

As shown in Table 2, the most important articulatory organs involved in the biting and chewing process are the tongue and jaw. Hence, when there is a child in speech therapy who has problems in this area, biting and chewing training should assume the stimulation of rotational and lateral movements of the tongue. To assess whether the functions of biting and chewing are going properly, the main skill that the therapist must check is the movement of the food onto the molars, which are used to comminute, crush or mill food. Chewing occurs in three planes and, unlike biting, applies to long-term processing of hard foods, e.g. meat (Skrzek, 2016, p. 354).

Biting and chewing

Table 2. The mechanism of biting and chewing

Biting Biting off

Jaw ■ ■ liftingreduction ■ ■ visiting and attendingsimilar to rotational movements

Tongue ■ food movement to the chewing sur-faces of the teeth ■ food movement, mixing with saliva

Other ■ from coordinated movements and irregular rhythms to smooth biting ■ respiratory coordination

Source: Own study based on: Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, pp. 92–93.

As Pluta-Wojciechowska reports in the publication Primary functions and articulation disorders (2013), “[…] observation of the development of eating skills that classic biting off and biting with teeth precedes the use of toothless gums, tongue and palate for softening and dissolving the food” (pp. 95–96). The infant learns to move food into different parts of the articulatory organ, to grind food on the palate or through the use of toothless gums and to soften food. The author of the activities that occur in a child who does not yet have milk teeth, proposes to name it in two different ways: pre-baiting off and pre-chewing or pseudo-bit-ing off and pseudo-chewpseudo-bit-ing. The above-described activities prepare the child for biting and chewing in a physiological way. It should be mentioned that during chewing, the coordination of such organs of the stomatognathic system like lips, cheeks and tongue is based on the key activity of the tongue, which by adopt-ing different shapes and positions transfers food, mixes it with saliva, formulates a bolus, placing it on the middle part of the muscle, and later during somatic swallowing, it lifts the apex to the space behind the upper teeth and, with peri-staltic movements, moves food towards the oesophagus (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, pp. 95–96).

Studies on the impact of the short frenulum on digestive activity have shown that it is the cause of incorrect sucking, chewing and swallowing, which in turn leads to speech disorders (Huang et al., 2015, p. 2). There are many cases of under-estimating the problem of ankyloglossia in newborn and infants, which in early childhood results in pronounced speech defects, which appear to be the result of a shortened tongue frenulum. As Sambor and Pluta-Wojciechowska (2016) point out in their publication, this situation may result from the fact that the child’s parents and doctors did not notice that the child did not perform any of the functions and therefore preferred to wait and not direct the child for frenotomy. However, one should know that “in assessing the course of biological functions, it is not only important that the child eats and breathes, but also how he eats and

The authors compare the movements of organs during biological activities to walking, while the movements of organs in articulation to dancing, which are more precise and sophisticated. Referring to this comparison, it can be stated that the one who knows how to march will not always be able to dance like a ballerina, hence when assessing such an important criterion as a frenulum, both the needs of basic primary functions and later articulation needs should be taken into account.

A good example of a study that proves the relation between primary and secondary activities is the study conducted by the speech therapist, Pluta-Wojciechowska “Children and adults with or without ankyloglossia and/or mal-occlusion”. It was attended by 40 people aged 4 to 30 who did not have problems with physical and phonemic hearing, cleft palate and lips, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, Down syndrome, speech delay and autism. In 36 patients, multiple disorders of phoneme realization were found, and only in 4 speech was com-pletely correct. The study showed that only one person had normal anatomical conditions, mainly malocclusion and tongue frenulum was found only in one person; 31 had ankyloglossia of varying sizes, and 22 had malocclusions. Based on the above data, some individuals had an associated anatomic defect (ankylo-glossia and malocclusion). By analysing individual physiological functions, it was shown that only 13 people had the correct position of the tongue during breath-ing and the correct breathbreath-ing, while the remainbreath-ing part revealed a low restbreath-ing position of the tongue, however, not all of them had an incorrect air intake path. The interview showed that problems with the right respiratory tract had already started among these people in the past. The author argued that in most patients, the reason for the speech impediment was the coupling of pathological, anatomi-cal motor (ankyloglossia, malocclusion) and functional (abnormal swallowing, breathing) factors, and primary compensatory strategies translated into similar strategies for compensating for secondary activities (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, pp. 293–296).

However, it should be remembered that the primary functions do not include only the activities described above. As Pluta-Wojciechowska reports, other non-verbal activities of the oral-facial complex are also primary activities, such as:

■ facial expressions; auto-stimulation;

■ orofacial self-games;

■ experiencing sensations from the oral cavity;

■ physiological activities, such as coughing and yawning;

■ other prenatal and postnatal activities (Malicka, 2013, p. 47).

In the functions described above, tongue does not play a major role, which is why it can be concluded that ankyloglossia does not affect the above-mentioned activities and does not disturb these functions.

Ankyloglossia in children – case study

This paragraph presents cases of three pre-school children who did not undergo frenotomy. All children have a significantly shortened frenulum. The effects of ankyloglossia on their functioning (breathing, sucking, swallowing and food func-tions) and their current situation are discussed. The following data comes from an interview with parents of children and an analysis of speech and medical docu-mentation. For publication purposes, all names of the children have been changed.

Case 1. Ania, 4 years old

According to the interview with the child’s mother and the analysis of medical records, the lack of frenulum undercutting was the result of incorrect biting off and swallowing. At the age of 9 months, the girl was choking a lot, there were prob-lems with biting off soft foods (despite her willingness, she could not cope with this activity), which her carers gave her. The situation improved around the age of 12 months of age, so that the parents calmed down a bit. Despite this, the carers did not decide to undercut the frenulum, as they themselves stated, out of fear of the surgery itself. Ania went to the kindergarten at the age of 3 and for a year she has performed exercises stretching the frenulum with the help of the speech therapist. According to her mother, the exercises did not change much for the child.

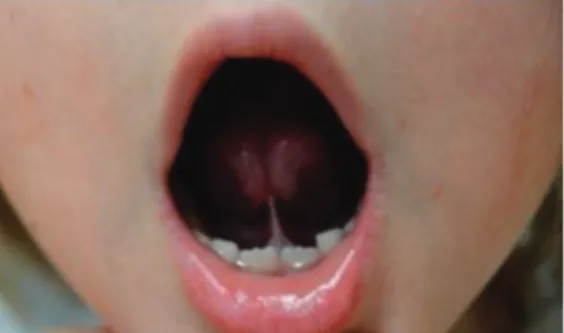

Illustration 1. Ania, 4 years old. Shortened frenulum – covering the upper lip with red tongue

Source: Archive of authors.

Illustration 2. Ania, 4 years old. Shortened lingual frenulum – an attempt to lift a wide tongue behind the upper dental arch

Case 2. Jaś, 3 years old

Jaś was born in the 38th week of pregnancy. From the very first days of the baby’s life, the mother felt pain during breastfeeding. She was also concerned that the boy often had colic and hiccups when drinking milk. After a few weeks, the mother noticed that the boy was not gaining weight and his milestones were moving. After meeting with the lactation counsellor, the mother fed the baby from the bottle and the boy’s sucking has significantly improved.

When Jaś was 2 months old, his mother was worried that the boy was breath-ing through his mouth both durbreath-ing the day and durbreath-ing sleep. The woman began to search for the answer to the question why this is happening on online forums. After reading the posts of other mothers who wrote that their children function in a similar way, claiming that there is nothing wrong this this, the mother of Jaś felt calm and stopped further interventions. At the age of 2, when the boy began to speak his first words, the parents noticed that his speech was blurred and differs from the speech characteristics of their friends’ children. However, when the boy reached 3 years of age, and his articulation became even more incomprehensible, terrified parents contacted a speech therapist, who recommended undercutting the frenulum and offered further therapy.

Illustration 3. Jaś, 3 years old. Short tongue frenulum – an attempt to lift the tongue up

Source: Archive of authors.

Illustration 4. Jaś, 3 years old. Shortened tongue frenulum – sticking out the tongue on the chin

Case 3. Michał, 5 years old

According to the interview, one week after birth, Michał began to learn to take food from the bottle, for his mother’s health reasons and because of the medicines she was taking. In his 6th month of life, the parents began to introduce pulpy foods to the boy, but Michał spit out meals served to him for a long time. Over time, the parents gave the boy soft food, which he ate selectively. The problems arose when the child received, for example, meat from a soup. The boy could not cope with chewing this dish (according to the paediatrician, the chewing mechanism was incorrect because it resembled biting with an open mouth).

At the age of 3, the parents decided to visit a speech therapist because they were worried about the slurred speech of their son. The therapist noticed that the boy breathes through his mouth and during speech speaks works during inhalation and exhalation, and very often and loudly draws air into the respira-tory tract. The speech therapist explained to his parents that the boy should have his frenulum undercut, because it is too short and all problems arise from this. The parents of Michał did not decide on the procedure, considering it too invasive.

Illustration 5. Michał, 5 years old. Shortened lingual frenulum – an attempt to lift a wide tongue behind the upper dental arch

Source: Archive of authors.

Illustration 6. Michał 5 years old. Shortened lingual frenulum – covering the red of the upper lip

Summary

The issue of ankyloglossia and its impact on primary functions has not yet been sufficiently exhausted. There are many inaccuracies in both Polish and for-eign sources regarding this topic.

It would be necessary to carry out studies that prove the possibility of the impact of the shortened frenulum on all basic physiological functions of the oro-facial system, or will negate it. In addition, it is important to introduce a single, common pattern of management for ankyloglossia. It is widely known that many speech therapists have different opinions regarding both the short frenulum, its function in the stomatognathic system, and the effects that are associated with ankyloglossia. Therefore, the cooperation of a speech therapist with other thera-pists and doctors is very important, because the short frenulum not only affects the faulty pronunciation, but also interferes with the primary activities described in this article, as well as contributes to the occurrence of anomalies in the bite, incorrect articulation or emotional problems. It is also worth paying attention to the fact that, against the background of other anatomical causes of incorrect pronunciation, ankyloglossia is an anatomical defect that is relatively easy to remove. Therefore, it is important to make parents and carers aware of the impact of ankyloglossia on the child’s development and problems that may arise in con-nection with its non-treatment.

Bibliography

Ballard, J.L., Auer, C.E., & Khoury, J.C. (2002). Ankyloglossia: assessment, incidance, and effect of frenuloplasty on the breastfeeding dyad. Pediatrics, 5, e63–e63.

Dezio, M., Piras, A., Gallottini, L., & Denotti, G. (2015). Tongue-tie, from embriology to treat-ment: a literaturę review. Journal of Pediatric nad Neonational Individualized Medicine, 4(1), 1–12. Huang, Y.S., Quo, S., Berkowski, J.A., & Guilleminault, C. (2015). Short Lingual Frenulum and

Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Children. Int J Pediatr Res, 1, 1–4.

Kaczmarek, A., & Łysiak-Seichter, M. (2005). Ankyloglosja i jej wpływ na powstawanie wad zgryzu, opis przypadków. Forum Ortodontyczne, 1(5), 133–141.

Kotlow, L. (2008). Lasers and pediatric dental care. Gen Dent, 56, 618–627.

Lingual, labial frenums: Early detection can prevent health effects associated with tongue-tie.

Retrie-ved from: https://www.rdhmag.com/articles/print/volume-35/issue-12/content/lingual-and- labial-frenums.html (access: 15.03.2019).

Łuszczuk, M. (2013). Zaburzenia czynnościowe w obszarze narządu żucia jako podłoże wad wymo-wy. Forum Logopedyczne, 21, 55–62.

Malicka, I. (2013). Oddychanie jako jedna z funkcji prymarnych. Forum Logopedyczne, 21, 47–54.

Martinelli, R., Marchesan, I.Q., Gusmão, R.J., Rodrigues, A., & Berretin-Felix, G. (2014). Histological Characteristics of Altered Human Lingual Frenulum. Int J Pediatrics and Child

Health, Health, 2, 5–9.

Nehring-Gugulska, M., Żukowska-Rubik, M., & Pietkiewicz, A. (2017). Karmienie piersią

w teorii i praktyce. Podręcznik dla doradców i konsultantów laktacyjnych oraz położnych, pielę-gniarek i lekarzy. Kraków: Wydaw. Medycyna Praktyczna.

Ostapiuk, B. (1997). Zaburzenia dźwięczności realizacji fonemów języka polskiego – propozycja terminów i klasyfikacji. Audiologia, X, 117–136.

Ostapiuk, B. (2005). Logopedyczna ocena ruchomości języka. In: M. Młynarska, & T. Smereka (Eds.), Logopedia. Teoria i praktyka (pp. 299–306). Wrocław: Wydaw. A. Linea.

Ostapiuk, B. (2013). Dyslalia ankyloglosyjna. O krótkim wędzidełku języka, wadliwej wymowie

i skuteczności terapii. Szczecin: Wydaw. Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego.

Ostapiuk, B. (2015). Postępowanie logopedyczne u osób z dyslalią i ankyloglosją. In: S. Gra-bias, J. Panasiuk, & T. Woźniak (Eds.), Logopedia. Standardy postępowania logopedycznego (pp. 655–685). Lublin: Wydaw. Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.

Pluta-Wojciechowska, D. (2011). Paradygmat postępowania w przypadku zaburzeń połykania w fazie ustnej. Ujęcie logopedyczno-ortodontyczne. Forum Logopedyczne, 19, 138–152.

Pluta-Wojciechowska, D. (2013). Zaburzenia czynności prymarnych i artykulacji. Bytom: Wydaw. Ergo-Sum.

Pluta-Wojciechowska, D., & Sambor, B. (2016). O różnych typach skróconych wędzidełek języka, ich ocenie i interpretacji wyników badań w logopedii. Logopedia, 45, 123–157.

Proffit, W.R., Fields, H.W., & Sarver, D.M. (2007). Contemporary orthodontics. St. Louis: Mols-by Elsevier.

Sioda, T. (2012). Wędzidełko języka u noworodka – ocena neonatologiczna i zalecenia. Stand Med

Ped, 9, 115–123.

Skorek, E.M. (2010). Reranie. Profilaktyka, diagnoza, terapia. Kraków: Impuls.

Skorek, E.M., & Rządzka, M. (2011). Profilaktyka i terapia dysfunkcji oddechowych u dzieci. Zie-lona Góra: Wydaw. Uniwersytetu Zielonogórskiego.

Skrzek, J. (2016). Diagnoza i terapia funkcji pokarmowych w obrębie okolicy orofacjalnej – poły-kania, gryzienia i żucia. In: S. Milewski, & K. Kaczorowska-Bray (Eds.), Wczesna interwencja

logopedyczna (pp. 337–354). Gdańsk: Wydaw. Harmonia Universalis.

Stańczyk, K., Ciok, E., Perkowski, K., & Zadurska, M. (2017). Ankyloglosja – przegląd

piśmien-nictwa. „Forum Ortodontyczne Warszawa”. Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny.

Stecko, E. (1991). Czynności przygotowujące niemowlęcy narząd artykulacyjny do podjęcia funk-cji mowy. In: B. Rocławski (Ed.), Opieka logopedyczna od poczęcia. Gdańsk: Wydaw. Uniwer-sytetu Gdańskiego.

Stecko, E. (2002). Zaburzenia mowy u dzieci – wczesne rozpoznawanie i postępowanie logopedyczne. Warszawa: Wydaw. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Suter, V., & Bornstein, M.M. (2009). Ankyloglossia: facts and myths in diagnosis and treatment.

J Periodontol, 80(8), 1204–1219.

Wallace, A.F. (1963). Tongue tie. Lancet, 2, 377–378.

Aneta Syta

Zakład Logopedii i Emisji Głosu, Uniwersytet Warszawski 0000-0001-7487-4083

Kinga Ziobrowska

Studentka logopedii ogólnej i klinicznej, Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny

Wpływ ankyloglosji na funkcje prymarne

Influence of Ankyloglossia on Primary Functions

Abstract: The aim of this article is to capture the influence of shortened tongue frenulum (anky-loglosia) on primary functions such as breathing, sucking, swallowing, as well as on food activities – biting and chewing. The publication is a review and is an attempt to combine the available profes-sional literature (national and world) on the above topic, as well as to discuss the conclusions from the cited studies. One of the paragraphs is devoted to several cases of children with ankyloglossia and its impact on primary activities in these children. The article also includes own reflections and considerations from the literature and case description discussed in the publication, children with shortened sublingual frenulum.

Key words: ankyloglossia, primary functions, tongue frenulum, vertical and horizontal position of the tongue

Skrócone wędzidełko podjęzykowe nie jest czymś, co w prosty sposób można zdefiniować i opisać. Obraz ankyloglosji jest niejednolity: u różnych osób wędzi-dełko może mieć różne poziom skrócenia, miejsce przyczepu, sposób usytuowa-nia względem samej powierzchni podjęzykowej (inaczej wędzidełka zewnętrzne lub ukryte pod śluzówką języka), kształt fałdu, elastyczność, sprężystość itd. W związku z tym może w różny sposób wpływać na jakość wymowy, a wcześniej na czynności prymarne. Ankyloglosja jest wadą anatomiczną, która ujawnia się tuż po urodzeniu i ma niebagatelny wpływ na funkcjonowanie dziecka w trak-cie późniejszego rozwoju. Mimo to do gabinetu logopedycznego częśtrak-ciej trafiają starsze dzieci, już ze złożonymi problemami związanymi właśnie ze skróco-nym wędzidełkiem. Aby temu zapobiec, ważne jest, by zarówno logopedzi, jak i pracownicy placówek medycznych, np. położne, umieli rozpoznać u noworod- ków krótkie wędzidełko i ocenić ryzyko negatywnych skutków w późniejszym czasie.

Ankyloglosja

Pierwsze zastosowanie terminu „ankyloglosja” pojawiło się w anglojęzycz-nej publikacji medyczanglojęzycz-nej, w latach sześćdziesiątych XX wieku, kiedy Anthony F. Wallace zdefiniował tongue-tie jako „[…] stan, w którym czubek języka nie może wystawać poza dolne zęby siekaczy z powodu krótkiego wędzidełka, czę-sto zawierającego bliznę” (Suter & Bornstein, 2009; Wallace, 1963). Na polskim gruncie opisywano również, że „[…] ankyloglosja (ankylosis ligule, ankyloglossia, ankyloglossia interior) to zaburzenie rozwojowe polegające na niedorozwoju wędzi-dełka języka i przyrośnięciu go do dna jamy ustnej, co uniemożliwia (utrudnia) jego poruszanie” (Ostapiuk, 1997, s. 132).

W literaturze medycznej można znaleźć informacje o tym, że wędzidełko języka jest fałdem tkankowym, który łączy dno jamy ustnej z dolną powierzchnią języka. Jest ono pozostałością embriologiczną, która powstaje na skutek niedokoń-czonej apoptozy występującej w uprzednim procesie oddzielania się masy języka od dna jamy ustnej. Jeżeli nastąpi zaburzenie wyżej opisanego zjawiska – język w umiarkowanym lub znacznym stopniu będzie przytwierdzony do dna jamy ustnej. Taka anomalia w budowie jest zwana ankyloglosją. Skrócone wędzidełko zazwyczaj jest wadą izolowaną, mimo to zdarza się, że współistnieje z niektórymi syndromami, np. Kindlera, Beckwitha Weidmanna, rozszczepem podniebienia sprzężonym z chromosomem X (Stańczyk, Ciok, Perkowski, & Zadurska, 2017, s. 124).

Częstość występowania ankyloglosji

Częstość występowania ankyloglosji jest trudna do ustalenia, ponieważ zależy ona od przyjętego kryterium oceny stanu wędzidełka. Jednak w kanonie publika-cji medycznych, logopedycznych można przeczytać, że wada ujawnia się częściej u chłopców niż u dziewczynek. Ta różnica w częstości występowania tłumaczona jest lepszą znajomością klasyfikacji i umiejętnością rozpoznawania ankyloglosji wśród personelu oraz traktowaniem krótkiego tylnego wędzidełka językowe-go – co przez wiele lat było nierozpoznawane i uznawane za normę – jako błąd w budowie języka (Sioda, 2012, s. 118). Ponadto wielu badaczy częstość występo-wania ankyloglosji wyznacza na 0,02 do 10,7% i wskazuje, że wada ta ujawnia się u chłopców od 1,5 do 3 razy częściej niż u dziewczynek (Ballard, Auer, & Khoury, 2002, s. 16; Stańczyk et al., 2017, s. 124; Suter & Bornstein, 2009).

Leczenie i rehabilitacja

W literaturze przedmiotu znaleźć można kilka propozycji leczenia krótkie-go wędzidełka podjęzykowekrótkie-go. Lokrótkie-gopedzi przedstawiają różne stanowiska, które według nich są odpowiednie, jednak do tej pory nie opracowano jednolitego sche-matu leczenia i rehabilitacji ankyloglosji. Wydaje się, że kontrowersje dotyczące leczenia ankyloglosji w ujęciu różnych autorów i badaczy są w głównej mierze związane z odmiennymi poglądami nawiązującymi do tzw. możliwości lub nie-możności rozciągania tej struktury.

Tabela 1. Stanowiska badaczy dotyczące rozciągania wędzidełka podjęzykowego Stanowiska dotyczące rozciągania wędzidełka podjęzykowego

Zwolennicy Przeciwnicy

Skorek, 2010 Kotlow, 2008

Stecko, 1991; 2002 Ostapiuk, 1997; 2005; 2013

Zaleski, 2002 Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013

Źródło: Opracowanie własne na podstawie: Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sambor, 2016, s. 134.

W powyższej tabeli przedstawiono tylko przykładowe nazwiska autorów, któ-rzy jako zwolennicy rozciągania wędzidełka poprzez masaż opisują znaczenie, jakie metoda ta ma dla poprawy funkcji oraz nawyków artykulacyjnych. Z tabeli można wywnioskować, że popierano ją w dużo starszych publikacjach. Nowsze natomiast ukazują negatywny wpływ masażu, jednocześnie zwracając uwagę na korzyści płynące z zabiegów chirurgicznych.

Warto zauważyć, że w publikacjach polskich, jak i zagranicznych nie opisuje się badań, które potwierdziłyby skuteczność masażu fałdu tkankowego w jego rozciąganiu. Co więcej, są doniesienia potwierdzające jego negatywne skutki. Roberta Martinelli i jej współpracownicy (2014) przeprowadzili badania nad strukturą wędzidełka podjęzykowego. Stwierdzili, iż zbudowany jest z fałdu błony śluzowej, w której skład wchodzą włókna kolagenowe typu I oraz włókna elasty-ny. Udowodnili, że te struktury nie podlegają rozciąganiu, wręcz są odporne na ten ruch i zapewniają możliwość powrotu do pierwotnej długości. Dzięki usytu-owaniu w wędzidełku takich włókien rozciągliwość nie jest możliwa w żadnym z rodzajów wędzidełek (przednie, tylne itp.).

Danuta Pluta-Wojciechowska i Barbara Sambor (2016, s. 127–131) zauważyły, że masaż może nieść negatywny skutek przejawiający się w naderwaniu ciągło-ści wędzidełka. Taką informację uzyskały z wywiadów zebranych od niektórych matek dzieci z ankyloglosją, które przez namowę logopedów masowały tę struk-turę i doprowadziły do pojawienia się krwi i obrzęku. Niechęć do wykonywania zabiegów chirurgicznych może wiązać się więc z przekonaniem niektórych

tera-peutów, jak i części specjalistów (ortodontów, pediatrów itd.), że zabieg podcięcia wędzidełka to wyrządzanie dziecku krzywdy.

„Chirurgiczne leczenie” wędzidełka u noworodków stosowane było już co najmniej 3 tysiące lat temu, poprzez naderwanie jego struktury paznokciem. Jak można zauważyć, „zabieg” ten odbiega w dużym stopniu od współczesnych metod leczenia, świadczy jednak o tym, że konsekwencje ankyloglosji w późniejszych czynnościach fizjologicznych były poznawane od lat. W Polsce ten problem został doceniony w 2012 roku, gdzie na V Zjeździe Centrum Nauki o Laktacji wpro-wadzono badanie wędzidełka i jego podcięcie do standardowego postępowania u każdego noworodka (Ostapiuk, 2015, s. 659–660).

Ze względu na budowę krótkiego wędzidełka wyróżnia się różne rodzaje lecze-nia: frenotomię, frenektomię, frenuloplastykę. U najmłodszych dzieci za wstęp-ne rodzaje leczenia uznaje się dwa pierwsze, które oznaczają kolejno: podcięcie wędzidełka i całkowite wycięcie wędzidełka. Zabieg frenuloplastyki, czyli różne metody jego korekty, uznawany jest za etap późniejszy. U noworodków frenoto-mia jest robiona bez znieczulenia, ale jest ono konieczne w przypadku starszych dzieci. W niektórych przypadkach jednorazowy zabieg nie wystarcza i często dodatkowe korekty są nieuniknione. Samo podcięcie wędzidełka nie rozwiąże od razu problemu, z którym dziecko zostało zgłoszone do zabiegu. Takimi powoda-mi są głównie problemy z karpowoda-mieniem dziecka, a tak naprawdę z niemożnością ssania przez dziecko mleka matki oraz w przypadku starszego dziecka – proble-my z wymową. W związku z tym bardzo ważne jest wykonywanie ćwiczeń przed zabiegiem i po nim.

Dla małego dziecka naturalnym ćwiczeniem wędzidełka jest oczywiście ssa-nie. Dziecko, po wykonaniu zabiegu, jest od razu przystawiane do piersi. Starsze dziecko, które wykształciło już mowę w większym lub mniejszym stopniu, wyma-ga prowadzonych przez logopedę ćwiczeń pionizujących język – zarówno przed zabiegiem, jak i po nim. Tak jak przy każdym innym zabiegu i tutaj występują przeciwskazania. Jeżeli noworodek ma problemy z krzepnięciem krwi lub wro-dzoną chorobę jednostki ruchowej, nie może być zakwalifikowany do zabiegu, ze względu na duże ryzyko przesunięcia języka w stronę gardła i spowodowanie zaburzeń oddychania i połykania (Sioda, 2012, s. 121–122).

Funkcje prymarne

Funkcje prymarne kształtują się na podstawie motoryki pierwotnej i należą do nich takie czynności jak: oddychanie, przyjmowanie pokarmów i picie. Trze-ba jednak wspomnieć, że termin ten nie ogranicza się wyłącznie do wypisanych wyżej funkcji. Mimika twarzy, autostymulacja, autozabawy w obrębie kompleksu

ustno-twarzowego oraz czynności fizjologiczne typu kasłanie i ziewanie – to ele-menty wskazujące na szersze znaczenie tego pojęcia (Malicka, 2013, s. 47).

Czas kształtowania się powyższych funkcji przypada na okres prenatalny. Ten etap to nie tylko modelowanie się konkretnej bazy wielotorowych czynności, ale również właściwy trening narządów, które z biegiem czasu będą brały udział początkowo w czynnościach prymarnych, a w późniejszym czasie w produko-waniu substancji fonicznej. W publikacji Pluty-Wojciechowskiej (2013, s. 55–56) opisane są badania, z których wynika, że do 16. tygodnia życia płodowego dziec-ko w ciągu dnia ujawnia odziec-koło 20 tysięcy różnorodnych ruchów, które występują również w obrębie twarzy i narządu żucia. Natomiast w drugiej połowie pierw-szego trymestru można zaobserwować wielorakie objawy, które pojawiają się w różnym czasie i są to przykładowo zwrot szyi i tułowia na bodziec wargi górnej, pobór, wypieranie i z czasem połykanie wód płodowych, możliwe jest wystąpie-nie ssania kciuka, co w wystąpie-niektórych przypadkach można zaobserwować podczas standardowego badania USG, oraz praca mięśni biorących udział w oddychaniu już poza łonem matki.

Oddychanie

Oddychanie to funkcja niezbędna do życia i jest ona odruchem bezwarun-kowym. Charakteryzując oddychanie, powinno brać się pod uwagę takie ele-menty jak: droga wdechu i wydechu, pozycja narządów artykulacyjnych oraz typ oddechu (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, s. 78–79). W mechanizmie oddychania wyróżnia się fazę wdechu oraz fazę wydechu. Irena Malicka (2013, s. 48) opisuje trzy sposoby oddychania: tzw. piersiowy, brzuszno-przeponowy (brzuszny) oraz brzuszno-piersiowy, czyli najefektywniejszy tor oddechowy, angażujący zarówno mięśnie klatki piersiowej, przepony, jak i brzucha.

Po porodzie zdrowy noworodek powinien oddychać torem nosowym. Jak pisze Urszula Kossakowska „[…] oddychanie przez nos jest jedynym sposobem fizjologicznego oddychania w pierwszych miesiącach życia człowieka” (Skorek & Rządzka, 2011, s. 15). Droga ustna uaktywnia się u osoby podczas oddechu dyna-micznego, gdzie występuje nasilony wysiłek fizyczny bądź podstawowa czynność mówienia. W takiej sytuacji powietrze pobierane jest zarówno torem ustnym, jak i nosowym (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, s. 79).

Ssanie

Pierwszym sposobem poboru pokarmu przez niemowlę jest ssanie. Jest to złożona czynność, która wymaga koordynacji ssania, połykania i oddychania (por. Przybyla, 2015, s. 578-580). Za tę synchronizację odpowiada w przybliże-niu aż 56 mięśni, 5 nerwów czaszkowych człowieka oraz nerwy rdzeniowe szyi i klatki piersiowej (Sioda, 2012, s. 117). Wielu autorów jest zgodnych, iż odruch ssania stopniowo zanika, za co jest odpowiedzialny szczególnie rozwój psychicz-ny i somatyczpsychicz-ny dziecka oraz progresywpsychicz-ny rozwój nerwowy (Łuszczuk, 2013, s. 59). Moment całkowitego zanikania tego odruchu przypada na około 12. miesiąc życia człowieka. Ważnym jest fakt, że do tego momentu dziecko uczy się przyj-mować pożywienie z łyżeczki, pić z kubka oraz odgryzać pokarmy o twardszej konsystencji (Malicka, 2013, s. 47).

Połykanie

Proces połykania towarzyszy człowiekowi od urodzenia, a nawet – tak jak zostało to opisane na początku niniejszego rozdziału – już w życiu płodowym. Aby rozwój czynności połykania przebiegał w sposób prawidłowy, szczególnie ważne jest właściwe funkcjonowanie zarówno obwodowego, jak i ośrodkowego układu nerwowego oraz zharmonizowanie pracy mięśni i oddechu. Według Wil-liama R. Proffita i Henry’ego W. Fieldsa człowiek połyka parokrotnie na godzinę w ciągu nocy, natomiast w dzień średnio 800 razy, co łącznie daje około tysiąca przełknięć na dobę. U człowieka występują trzy fazy połykania: ustna, gardłowa, przełykowa. Pierwsza faza jest zależna od woli, natomiast dwie pozostałe przebie-gają w sposób niekontrolowany (Proffit, Fields, & Sarver, 2007, s. 344).

Ważne jest to, iż proces połykania u dzieci i u dorosłych nie jest taki sam. Transformacja sposobu połykania z trzewnego (infantylnego, dziecięcego) na somatyczne (dojrzałe) dotyczy rozwoju układu stomatognatycznego, związanego z niwelowaniem fizjologicznego tyłożuchwia, pojawieniem się już większej ilości zębów mlecznych oraz wydłużeniem twarzy w odcinku dolnym. W literaturze przedmiotu występują dysonanse dotyczące czasu, w którym dziecko powinno oddychać już w sposób dojrzały. Za początek połykania somatycznego przyjmu-je się przyjmu-jednak okres trzeciego roku życia (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2011, s. 140–141).

Odgryzanie

Czas pojawienia się siekaczy mlecznych, przypadający pomiędzy 8. a 10. mie-siącem życia, to początek ujawnienia się czynności odgryzania. Należy wiedzieć, że nie ma kilku sposobów odgryzania. Zarówno dorosłych, jak i dzieci obowiązuje jeden i ten sam mechanizm, który nie zmienia się z biegiem dojrzewania człowie-ka. Rytm czynności wykonywanych w tym procesie pojawia się w określonej kolej-ności. Z początku żuchwa obniża się i występuje ustawienie brzegów siecznych siekaczy górnych i dolnych naprzeciw siebie, następnie skurcz mięśni powoduje, że opisane wyżej struktury ślizgają się względem siebie i następuje odgryzienie stałego kęsa. Logopeda powinien umieć ocenić sposób odgryzania przez dziecko i wiedzieć, że wszelkie inne miejsce poza płaszczyzną siekaczy górnych i dolnych wykonania tej czynności jest już zaburzeniem (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, s. 90).

Gryzienie i żucie

Kolejnymi funkcjami prymarnymi, które ujawniają się po opanowaniu czyn-ności odgryzania, są gryzienie i żucie. Czas, w którym czynność gryzienia zaczyna się kształtować, równy jest etapowi wyżynania się kolejnych zębów mlecznych, natomiast żucie pojawia się po treningu gryzienia, zazwyczaj wraz z pojawieniem się zębów trzonowych (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, s. 92–93).

We wczesnym okresie życia dziecka logopeda może ocenić umiejętność opi-sanych wyżej funkcji, biorąc pod uwagę odruchy związane z tymi czynnościami. Pierwszy z nich to odruch kąsania, który można zaobserwować u dziecka od uro-dzenia do nawet 4. a w skrajnych przypadkach 7. miesiąca życia. Aby ocenić ten odruch, należy położyć opuszki palców na górne dziąsła w okolicy kłów. Prawi-dłową reakcją na taki bodziec jest rytmiczne opuszczanie i wznoszenie żuchwy. Natomiast odruch żucia, który jest powiązany z odruchem kąsania, swoje początki ma w 4. miesiącu życia.

Dotyk warg, zębów lub jamy ustnej powoduje ruchy żuchwy w płaszczyźnie pionowej, tzn. ruchy odwodzące i przywodzące. Jednakże Pluta-Wojciechowska podaje, że gryzienie i żucie różni ruch wykonywany w innej liczbie płaszczyzn. W przypadku gryzienia są to dwie płaszczyzny powstające na skutek unoszenia i obniżania żuchwy, natomiast żucie wymaga ruchów w trzech płaszczyznach, w których dwa pierwsze odpowiadają ruchom podczas gryzienia, a trzeci to tzw. ruch żuchwy na boki (Skrzek, 2016, s. 348).

Wtórna różnica między gryzieniem a żuciem polega na konsystencji obrabia-nych pokarmów. W przypadku funkcji żucia są one znacznie bardziej twarde oraz

mają specyficzną architekturę. Zatem można wywnioskować, że funkcja żucia uaktywnia się wtedy, gdy gryzienie jest niewystarczające, a pokarmy powinny zostać dodatkowo zmiażdżone, co wymaga użycia większej siły i aktywności narządów artykulacyjnych (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, s. 93–94).

Wpływ ankyloglosji na czynności prymarne

Żeby zrozumieć istotę niniejszego paragrafu, należy wstępnie poznać mecha-nizm działania określonych funkcji prymarnych, wiedzieć, że język jest jednym z najważniejszych narządów biorących udział w większości czynności układu stomatognatycznego oraz że konsekwencją anomalii jego budowy, w tym głów-nie skrócone wędzidełko, będzie brak pionizacji tego mięśnia (inaczej zaburzona pozycja wertykalno-horyzontalna) oraz ograniczenie jego ruchomości (Kaczma-rek & Łysiak-Seichter, 2005, s. 134; Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sambor, 2016, s. 142; Stańczyk et al., 2017, s. 123).

Poza opisanymi wcześniej możliwymi analizami znaczenia skróconego fałdu tkankowego u noworodków i niemowląt dodatkową pomocą może być badanie przedstawione przez Plutę-Wojciechowską, które jest oceną anatomiczno-funk-cjonalną. Najważniejszym wnioskiem, który autorka wysnuła, analizując funkcje oddychania, jedzenia i picia oraz połykania, jest to, iż pozycja wertykalno-hory-zontalna to najważniejsza pozycja mięśnia biorąca udział w oddychaniu oraz somatycznym połykaniu (Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sambor, 2016, s. 135–136, 141). Podkreślano także, że krótkie wędzidełko językowe modyfikuje pozycję języka, szczególnie we wczesnym okresie życia oraz upośledza rozwój oralny (Huang, Quo, Berkowski, & Guilleminault, 2015).

Żeby zrozumieć sposób, w jaki krótkie wędzidełko wpływa na ruchomość i pracę języka, należy wiedzieć, że:

■ fragmenty poszczególnych mięśni są ze sobą połączone w różnych częściach, a aktywność poszczególnych mięśni języka wpływa na aktywność całego narządu;

■ język jest narządem artykulacyjnym o tej samej objętości, ale zmiennym kształ-cie;

■ ograniczenie ruchu narządu nawet w jednym kierunku powoduje ruch

całe-go języka w rozbieżny sposób (udział mięśni wewnętrznych i zewnętrznych języka);

■ od wykonania określonej czynności języka w prawidłowy sposób zależna jest skoordynowana i niezakłócająca praca wszystkich mięśni języka (Pluta-Woj-ciechowska & Sambor, 2016, s. 152).

Ankyloglosja a oddychanie

„Istnieją doniesienia o częstym współwystępowaniu ankyloglosji z przemiesz-czeniem nagłośni oraz krtani objawiające się u noworodków dusznością oraz defektami skóry, a u dorosłych – niewydolnością oddechową oraz chrapaniem” (Stańczyk et al., 2017, s. 131). W literaturze przedmiotu wyróżnia się dwa czyn-niki patologicznego oddychania torem ustnym. Są to czynczyn-niki ogólnoustrojowe oraz miejscowe. Do czynników miejscowych zalicza się zaburzenia powodujące całkowitą lub częściową niedrożność nosa, a także m.in.: przyrośnięte wędzideł-ko języka, krótka warga górna, wady zgryzu, makroglosja oraz hipotonia mięśni (Łuszczuk, 2013, s. 56).

Znajdująca się w gardle podstawa języka ma zdolność kształtowania jego mięśni. Natomiast część języka, która umiejscowiona jest w środku jamy ustnej, ma kluczowe znaczenie dla rozwoju szczęki, kształtu twarzy i dróg nosowych w górnych drogach oddechowych. Nieprawidłowa budowa języka powoduje zabu-rzenia czynności mięśni twarzowych, co w następstwie prowadzi do problemów z drogami oddechowymi, m.in. do obturacyjnego bezdechu sennego (Lingual, labial frenums…).

Ankyloglosja a ssanie

Ssanie to jedna z funkcji prymarnych, która wymaga jednoczesnej aktywno-ści wielu narządów artykulacyjnych. Do tych struktur należą przede wszystkim wargi, język oraz żuchwa (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, s. 95). Mechanizm pracy języka jest niezwykle istotny w samym procesie ssania piersi. W akcie ssania język wykonuje kilka różnych ruchów: przytrzymuje brodawkę sutkową, łącznie z policz-kami wytwarza w jamie ustnej podciśnienie oraz pokrywa krawędź zębodołową żuchwy i wykonuje ruchy protruzyjne, retruzyjne oraz perystaltyczne. W sytu-acji, gdy ruchomość języka jest ograniczona poprzez występowanie ankyloglosji, naturalne zdolności przystosowawcze noworodka mogą nie wystarczać i w efekcie pojawi się zaburzenie funkcji języka, co spowoduje nieprawidłowe ssanie piersi lub całkowitą niemożność wykonania tej czynności (Sioda, 2012, s. 116–117).

Z szacunków wynika, że blisko 13% problemów związanych z karmieniem może być uzależnionych od nieprawidłowej budowy wędzidełka językowego. „Niemowlęta z krótkim wędzidełkiem nie potrafią wysuwać języka dalej niż do dolnego wału dziąsłowego i albo dociskają wałami dziąsłowymi na brodawkę sutkową, albo uciskają wałami podstawę brodawki i nie potrafią jej utrzymać” (Stańczyk et al., 2017, s. 126).

W publikacji Magdaleny Nehring-Gugulskiej, Moniki Żukowskiej-Rubik i Agnieszki Pietkiewicz (2017, s. 7) można przeczytać, że gdy wędzidełko przed-nie jest skrócone, obserwuje się przed-niemożność ustabilizowania piersi oraz wytwo-rzenia podciśnienia niezbędnego do efektywnego pobierania mleka przez nie-mowlę. W efekcie może towarzyszyć temu nagryzanie piersi i cmokanie. Jak zauważają autorki, nie każdy typ ankyloglosji uniemożliwia ssanie piersi. Podob-ne stanowisko zajmują Pluta-Wojciechowska i Sambor (2016, s. 134), których badania wykazały, że wiele niemowląt z ankyloglosją potrafiło ssać, jednak w przyszłości występowały u nich wady wymowy. Warto zauważyć, że nie jest ważne tylko to, że dzieci ssały, ale również sposób, w jaki tę czynność wyko-nywały.

W literaturze anglojęzycznej pojawiły się badania, które miały na celu spraw-dzenie, czy obecność ankyloglosji wpływa na proces karmienia piersią. Jednym z takich analiz jest badanie wykonane przez naukowców z Katedry Pediatrii Uni-wersytetu Medycznego Cincinnati w Ohio, które objęło 2763 karmionych piersią niemowląt, w tym 273 ambulatoryjne niemowlęta z problemami z karmieniem piersią pod kątem możliwej ankyloglosji, i oceniono każde dziecko z ankyloglo-sją, używając narzędzia oceny ryzyka dla funkcji językowej wędzidełka. Badacze obserwowali każde dziecko w chwili karmienia piersią. W sytuacji, w której poja-wiały się problemy z zaciskaniem zębów dziecka na piersi, matki musiały opisać odczucie i jakość ssania piersi przez niemowlę oraz jeśli wystąpił ból, scharak-teryzować go w skali od 1 do 10. Jeśli u któregoś dziecka rozpoznano problem ankyloglosji, matki wyrażały zgodę na przeprowadzenie swoim dzieciom zabiegu frenotomii. Wyniki ukazały, że skrócone wędzidełko występowało u 88 (3,2%) pacjentów hospitalizowanych oraz u 33 (12,8%) dzieci ambulatoryjnych. Po wyko-nanym zabiegu frenotomii zatrzask poprawił się we wszystkich przypadkach, a poziom bólu u matek znacznie spadł (Ballard et al., 2002).

Ankyloglosja a połykanie

Język jest podstawowym narządem biorącym udział w połykaniu. Opisano już wcześniej dwa typy połykania, do których zaliczało się połykanie trzewne, inaczej infantylne, oraz somatyczne, tzw. dojrzałe. Drugie z nich wymaga usta-wienia języka w pozycji wertykalno-horyzontalnej. Pozycja ta wymaga pioniza-cji szerokiego języka, gdzie jedna jego część jest wzniesiona i apex przylega do brodawki przysiecznej znajdującej się za szyjkami zębów siecznych, przy czym mediodorsum przyklejone jest do podniebienia, a boki języka przylegają do gór-nych zębów trzonowych i przedtrzonowych, z drugiej zaś strony język przyjmuje kształt szeroki (Pluta-Wojciechowska & Sambor, 2016, s. 136).

Należy wiedzieć, że gdy język znajduje się w opisanej wyżej pozycji, powoduje tworzenie sił podobnych jak w przypadku skurczającego się mięśnia. Ponadto, łącznie z krótkim wędzidełkiem, mięsień gnykowo-językowy modyfikuje prawi-dłową pozycję mięśnia bródkowo-gnykowego z wynikającym z tego podwyższe-niem i przesunięciem w przód kości gnykowej. W dynamicznej sytuacji ankylo-glosja ogranicza możność wykonania określonych ruchów niezbędnych w procesie połykania, co powoduje różne konsekwencje, w szczególności:

■ krótkie wędzidełko podjęzykowe działa jak przednie, anatomiczne ogranicze-nie dla mięśnia dwugłowego i mięśnia dwubrzuścowego, które podczas skurczu nie może przesuwać kości gnykowej w prawidłowy sposób;

■ język nie może uderzyć w podniebienie twarde, ale pozostaje przywiązany do dna jamy ustnej;

■ mięśnie podgnykowe nie mogą wykonywać stabilizacji kości gnykowej, a to powoduje nieprawidłową fleksję kręgosłupa szyjnego i głowy (Dezio, Piras, Gallottini, & Denotti, 2015, s. 5).

Zatem prawidłowy proces połykania to nie tylko pionizacja przedniej czę-ści szerokiego języka, ale również innych częczę-ści oraz rola wielu mięśni, głównie zewnętrznych języka, które koordynują pracę całego mięśnia, by bolus został prze-mieszczony do przewodu pokarmowego. Pluta-Wojciechowska (2013) wyróżnia czynniki, które korzystnie wpływają na transformację połykania z trzewnego na somatyczny, a jednym z nich jest „prawidłowa budowa języka, w tym jego wiel-kość oraz stan wędzidełka języka” (s. 105).

Ankyloglosja a czynności pokarmowe

Odgryzanie

Proces odgryzania został już wcześniej opisany, mimo to należy przypomnieć, że język w owym procesie odgrywa znaczącą rolę. Istotne aspekty czynności odgryzania to przede wszystkim praca mięśni unoszących i obniżających żuchwę, praca języka polegająca na przemieszczaniu pokarmu oraz koordynacja odde-chowa (Pluta-Wojciechowska, 2013, s. 90). Rozwój umiejętności odgryzania jest stymulowany poprzez podawanie przez rodzica dziecku coraz twardszych pokar-mów. „Podczas wykonania opisanej czynności odgryziony przy pomocy zębów siecznych pokarm musi być umieszczony na środkowej części języka, w wyniku czego możliwe jest wykonanie ruchu pionizacyjnego apexu” (Skrzek, 2016, s. 353).